What facts I can find vary. There aren’t that many secondary sources on the subject to begin with, which means that I’m going to have to do some real digging in the future in order give a more detailed account of what happened. That being said, I have the bones of the story, which goes something like this:

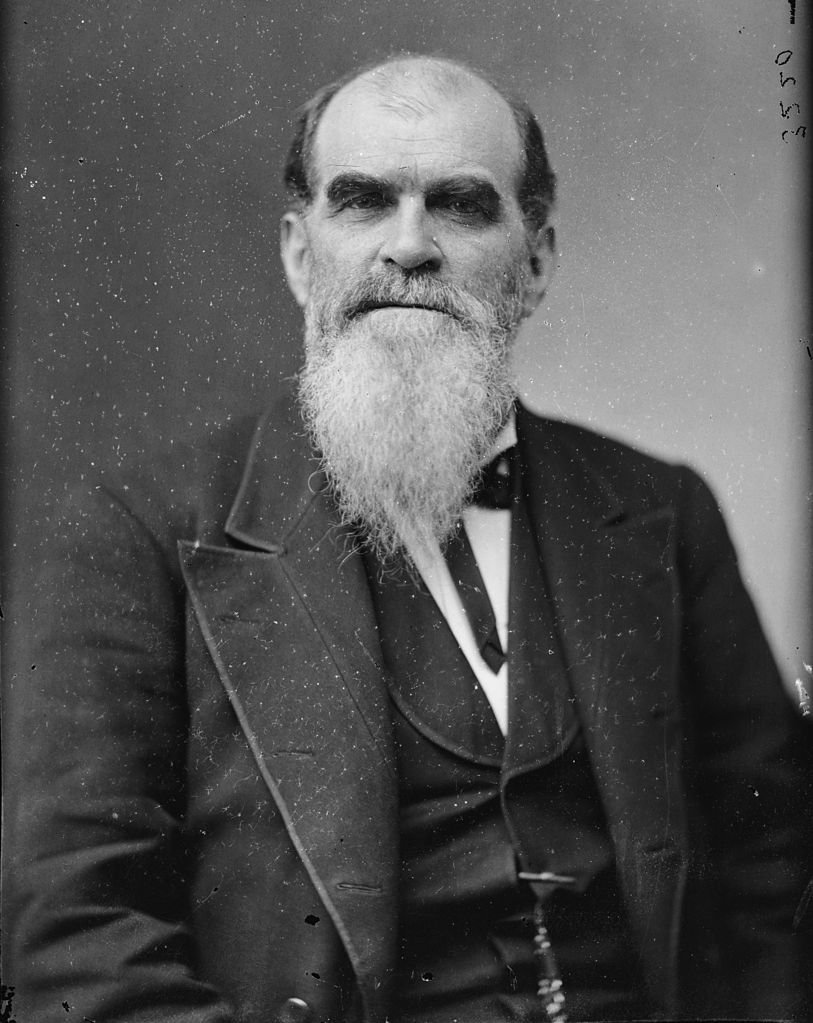

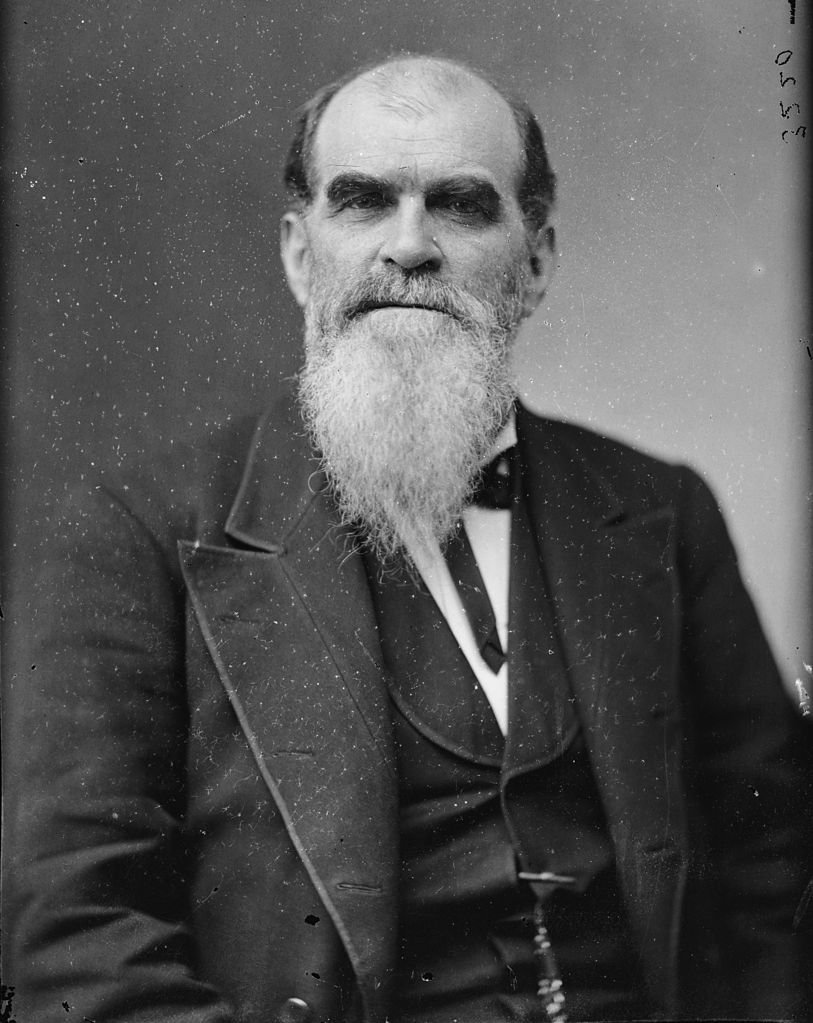

In January, 1874, Richard Coke, a scary-looking man six feet, three inches in height, used a combination of ladders and guns to gain access to the second floor of the Texas State Capital Building and unilaterally and illegally declared himself the governor of the state, which led to the end of Reconstruction in Texas and also built a Democrat coalition that ruled the state for more than a century.

(That’s him!)

I want to point out a couple of things.

First, this is super intense and kinda cool. If you’re the type that was wishing pirates got covered more in history, this might have been right up your alley.

Second, as someone who grew up in Texas and went to public schools, I can tell you that this was never covered in class. I’m fairly certain that it was not even alluded to. We’ll get to why that might be in a moment.

Like many things in U.S. history, this series of events came about in part due to the Civil War. When the war ended many abolitionists found themselves aligned with the Radical Republicans, a group which was in favor of Reconstruction, which largely involved protecting the rights of the newly-freed Blacks in the South and preventing former Confederates from gaining political power.

This was difficult to do without Federal intervention, as former Confederates were able to form powerful coalitions that steamrolled elections, often on platforms that were in direct opposition to the Radical Republican platform.

When the war ended, Andrew Jackson Hamilton, who had fled the state when war broke out, was appointed by Andrew Johnson as the governor of Texas. His term lasted a year until elections were held in 1866 when James W. Throckmorton was elected. As the area was still under martial law, and Throckmorton was opposed to reconstruction, U.S. General Philip Sheridan removed him from office and replaced him with Republican Elisha M. Pease.

Pease was incompetent and managed to lose support from both Republicans and Democrats, leading to his resignation in 1869.

Radical Republican Edmund J. Davis was elected in the same year as his replacement, defeating former governor Andrew J. Hamilton. Davis raised a group of volunteers from Texas to fight for the Union during the war, and eventually reached the rank of Brigadier General.

Davis was a strong proponent of Reconstruction and for civil rights for African Americans. Consequently, he was very unpopular with Democrats.

In December 1873, he ran for reelection against Democrat Richard Coke.

The outcome was either 100,415 to 52,141 in favor of Coke or 85,549 to 42,663, also in favor of Coke.

By all rights, Richard Coke should have been governor, however, there were a number of problems with the 1873 election. There were widespread allegations of voter fraud and voter intimidation.

It is possible that these allegations might not have mattered if it were not for the Ex Parte Rodriguez court case.

Joseph Rodríguez was arrested on suspicion of voting more than once in the election. A crack legal team of Republicans, including former governor Andrew J. Hamilton, defended Rodríguez in a case that worked its way up to the Supreme Court of Texas.

Their defense?

The election itself was unconstitutional, therefore Rodríguez could not be charged with a crime.

The Supreme Court agreed with them, interpreting a semicolon in the state constitution in such a manner as to suggest that the legislature could not change the rules around elections.1

The constitution dictated that voting would take place over four days in the cities that were county seats. The legislature had decided that the election would be held on a single day and that voting locations could be held outside of county seats.

Consequently, the election itself was declared unconstitutional, which meant that the incumbent, Edmund Davis was still governor, despite having lost the election. It’s worth pointing out that the current sitting judges had been appointed by Davis.

Obviously, Richard Coke and his supporters didn’t like this decision. So, they decided to ignore it.

Davis, who was still technically governor, barricaded himself in the lower floor of the State Capitol. Davis called in the state forces in order to protect himself and his position, and also appealed to then-President Ulysses S. Grant for Federal aid.

One of the local units called in to protect Davis was the Travis Rifles.

And as it turned out, they preferred Coke to Pepsi, er, Davis, and formed a sheriff’s posse so that they might help Coke gain the governorship. This group, along with other Coke supporters snuck onto the second floor of the Capitol and locked the doors.

This situation apparently lasted from January 15th, when Richard Coke was inaugurated, until the 19th, when Davis, now certain that he would not receive federal aid, resigned.

Technically speaking, the lieutenant governor was next in line and should have become the next governor.

But, this wasn’t a moment for rules.

In fact, given that Coke wasn’t technically legally elected, and he took office by force arms, this situation might represent the only successful military coup in U.S. history. Which is pretty crazy when you think about it.

So, why was this never mentioned?

Most, or maybe all, of it is because the Democrats were quite racist at the time. Their electoral success was due in part to racism. Implicit and sometimes explicit condoning of racist behavior in public, as well as voter suppression by both the enactment of Jim Crow laws and voter intimidation by organizations like the KKK meant that the Democrats would hold both national senators until 1962, the governorship until 1979, the state senate until 1999, and the house until 2003.

Certainly, there are other factors, including demographic changes and shifts in the party policies. But, there was also racism. And, unfortunately, it’s hard to accurately rank these factors in terms of importance and effect. It’s not good, but it’s also a product of the times, and I will leave it at that since the topic could use an article of its own.

So, let’s put things in context.

Richard Coke was a likely racist.

However, he did go good things for the state. In his role as governor, he helped create Texas A&M, helped rewrite the state constitution, which still stands to this day.

This constitution was especially important because it reformed a previous fund into the Texas Permanent School Fund, to which the state contributed half its public lands, with the thought that revenue from grazing and ranching performed on the lands could be used to fund schools.

The discovery of oil on these lands has sent the value of the fund into the stratosphere. Today it is worth $41.44 billion, and it is projected to disburse $2.5 billion to Texas schools during the 2018-2019 biennium. That’s not shabby at all.

At the end of the day, Coke’s legacy is certainly mixed.

There’s the good, the bad, and the guys that deputize the military in order to seize the governor’s office.

If you liked this article, you might like:

881 Priests

43,000 Employees and no Sherlock Holmes

When Statues Attack