Is Globalism Dying?

Across the world, things are changing.

This is always true, but right now there are a couple of significant events that appear to be challenging the old order. Not only were these occurrences considered unlikely, but by many, they were considered impossible.

The election of Donald Trump.

Brexit.

The U.S. withdrawal from the Trans-Pacific Partnership and the Paris Climate Agreement.

The recent election success of the right-leaning, Eurosceptic parties Five Star and Lega Nord in Italy. Together they have enough seats to form a coalition government, which in theory could initiate Italexit.

Five years ago, much of this wasn’t even on most people’s radar. It certainly wasn’t on mine, even as the tide started to shift.

The previous U.S. President, Barack Obama, was a proponent of both the Trans-Pacific Partnership, even though it brought him into conflict with his base. Amazingly, he didn’t seem to realize the tide was shifting, either.

What is going on? Has the world collectively lost its mind?

Well, the second question presumes that it was ever sane to begin with. The first is much more answerable.

What all of these events have in common is that they are anti-globalization. A reactionary movement, if you will. Though, to be fair, all movements are a response to something, and thus must be reactionary.

First, I want to stress that both globalization and the reaction to it are nothing new. Advances in technology in the 19th century such as the telegraph and telephone brought the world closer together, and advances in technology made shipping goods from one country to another both faster and more cost-efficient.

After World War II, the creation of the World Trade Organization (WTO) accelerated the process.

Some of the WTO’s goals include the following.

Promotion of free trade:

- Elimination of tariffs; creation of free trade zones with small or no tariffs

- Reduced transportation costs, especially resulting from development of containerization for ocean shipping.

- Reduction or elimination of capital controls

- Reduction, elimination, or harmonization of subsidies for local businesses

- Creation of subsidies for global corporations

- Harmonization of intellectual property laws across the majority of states, with more restrictions

- Supranational recognition of intellectual property restrictions (e.g. patents granted by China would be recognized in the United States)

In short, people started looking at the economy differently. Instead of looking at it on a national, or perhaps regional, level, they instead started looking at it as a cohesive global unit. Consequently, much of globalization is dependent on removing “friction” in global trade, making it easier for multinational corporations to move both goods and jobs from one country to another.

Along the way, many have made the case that this is an exceptionally good thing.

According to a Forbes article, “[s]upporters of globalization argue that it has the potential to make this world a better place to live in and solve some . . . deep-seated problems like unemployment and poverty.”

The various promised benefits vary. In fact, I’ve struggled to find a cohesive list, despite my research. The best I can give you is sort of a summary of things that people seem to advocate for.1

In short, globalization is the promise that free trade will create jobs and lower prices for everyone in the world. It will also promote democracy, spread information and technology, promote understanding between different peoples through increased contact, and help third-world countries develop.

If this sounds utopian, well, that’s because it is a utopian vision.

If I were to go out on a limb, I’d suggest that globalism can’t succeed, only because it is utopian. Utopian systems fail because they promise a lack of pain, and causing pain is inevitable in any system. They doubly fail if they are perceived as causing more pain than other systems.

So, how is globalism causing pain?

For starters, “it has made the rich richer while making the non-rich poorer,” and “jobs are lost and transferred to lower cost countries,” meaning that developed countries lose jobs to under-developed countries.

Consequently, two groups of people benefit most from globalization: business owners in rich countries, who are able to realize fantastic profits, and workers in poor countries, who due to being willing to accept less pay for the same labor are given increased access to jobs by multinational corporations.

Who loses out?

Workers in wealthy countries.

Okay, but why now? Why have the last three or so years produced a number of politicians and political movements that reject globalization, even as the economic pressures have existed for the better part of 80 years?

Well, the two decades going into 2008 weren’t great ones for many people. The “global upper middle class – those between the 75th and 90th percentiles on global income distribution, of whom 86% were from advanced economies,” “particularly lost out on relative gains in income.”

Furthermore, “increased global trade has played a role in economic stagnation or decline . . . especially in the US.” And these quotes are taken from an article written in 2008 and doesn’t touch on the Great Recession.

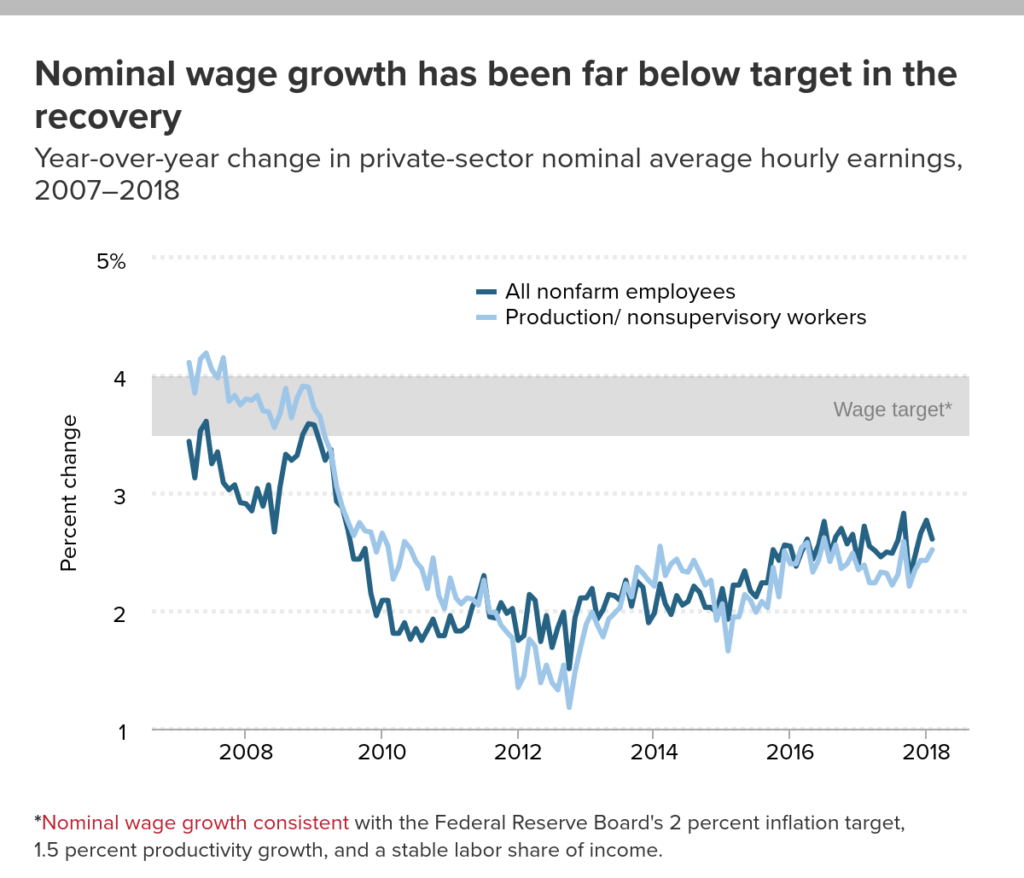

Since that time, wages have only grown very slowly:

https://www.epi.org/nominal-wage-tracker/

However, there have been times over the same span where inflation has equaled or outpaced wage growth. Here’s a chart for comparison:

http://www.usinflationcalculator.com/inflation/current-inflation-rates/

When this happens, growth in wages is offset by the currency losing value. Even if you make more money, you have less purchasing power.

This concept is called “real wage growth,” and it’s been pretty sucky over the last decade. According to a recent Bureau of Labor Statistics report, real wages grew .4% from February 2017 to February of 2018. That’s not going to make much of a difference in most people’s lives.

Compare that to the 2.6% growth experienced annually between 1996 and 1999, which while more significant, was still down 3.1% from 1989. In short, people have gotten poorer, or at least, not benefited much form economic growth over the last few decades, even as the companies they work for have realized historically-unprecedented profits. This pattern has intensified since 2008.

This is why phrases like “Make America Great Again,” hold so much power. This is a problem that can’t be fixed alone. People know something is wrong, and even if they don’t have a ready solution, they’re willing to vote for something who is willing to mix things up, because the status quo is untenable.