If you were ever looking for a sign that I tend to run a bit behind the times, then this article is exactly what you’re looking for. In fact, I’m getting around to this topic almost three full months after it became relevant and while you could suggest that I’ve been using this time to hone my argument or do more research, it’s just not true. I had forgotten about it until recently, when I was looking through my list of potential blog posts and was the topic sitting there, lonely and now quite late.

But, looking at the news articles published about the event in question, which were mostly published in a clump in the week after November 2nd, it seems the world has largely forgotten about the event. It was at the top of the Internet on the 2nd and gone by the 3rd, which is probably why I forgot about it as well.

But, what are you talking about?

Glad you asked.

I’m talking about the U.S. withdrawal as an implementing member of E.I.T.I.

What is E.I.T.I.?

Created by former UK Prime Minister Tony Blair, the Extractive Industries Transparency Initiative is an organization that hopes to lower corruption in resource-rich countries. This is accomplished by getting oil and other natural-resource companies to publish what they pay to governments in taxes and fees. A discrepancy between the companies’ reported number and that reported by the government would suggest that government corruption is taking place, as one of the easiest ways to funnel money into personal accounts is never to report that it got to the government in the first place.

So, after hearing that the U.S. was going to stop implementing E.I.T.I. and reading up on what it was, it seemed like it wasn’t that big of a deal. My gut feeling was that the U.S. wasn’t terribly corrupt. If it’s not corrupt, then programs designed to prevent corruption are merely wasteful. Right?

Well, the rest of the world doesn’t see it that way. Part of the problem is that it fits a political narrative. Something like “Trump is corrupt; therefore, Trump’s actions are corrupt; therefore Trump removing anti-corruption rules is a path to self-enrichment.”

This line of thought was compounded by initial misreporting by Reuters, which initially reported that the U.S. was completely withdrawing from E.I.T.I., instead of just domestically. An article published by Forbes suggests that the withdrawal means that the U.S. is no longer “actively participat[ing] in anti-corruption initiatives.” 1 This awful article admits E.I.T.I.’s domestic shortcomings, but then tries to say that the U.S. should stay within E.I.T.I. because of the improvements it causes internationally, a conclusion disputed by other authors on the same site!2

The problem is that all of these assessments are completely wrong.

You see, the day it happened, the E.I.T.I. issued a statement that said “The Government of the United States is no longer an implementing country, but it remains a supporter of the EITI internationally. Supporting governments are committed to promoting good governance in the extractive industries across the world. A supporting country can support the EITI through financial, technical and political support at the international . . .” Put another way, while the rules will no longer be enforced domestically, the U.S. will continue to help other countries who wish to put them into practice.

As Bloomberg reports “the overall cost of the program and a dispiriting lack of attention to it” as well as “already strong anti-corruption measures built into U.S. law,” likely meant that “the government . . . felt it was unnecessary and expensive.”

This sounds like one of the excessive regulations that Trump promised to cut. And since the international commitments are remaining the same, E.I.T.I. was only having a domestic impact if there was a significant level of corruption within the U.S. Obviously, that’s what we need to find out next: Just how corrupt is the U.S.?

Quick side note: corruption is hard to measure, in large part because you can’t just poll people and ask if they took bribes or engaged in nepotism, as smart people will always answer “no” to those questions. Consequently, the best available data we have is based on estimates made by experts at Transparency International. This has two problems:

- Experts trained to sniff out corruption more likely to overestimate than underestimate, because they’re trained to guess at what they’re not seeing.

- It’s a freaking estimate!

Okay, moving on.

The good news is that the U.S. is not terribly corrupt. Ranked at 18th in the world, or just outside the top 10%, the U.S. is actually quite good in this regard. Exiting E.I.T.I. shouldn’t have much of an impact, if any.

But, while we’re on the topic of transparency, I feel the need to point out that Transparency International, well, isn’t.

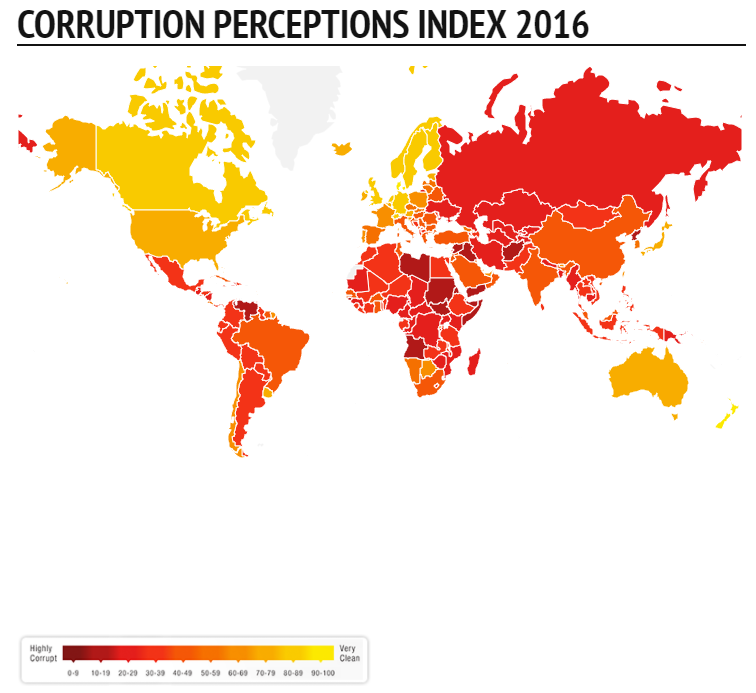

Take a look at this map they published in their annual report last year:

There are a couple of things I want to point out. First, Australia and the U.S., despite being 13th and 18th in the world, are colored a sickly shade of orange that suggests they are on the edge of dropping into serious corruption at any moment, which just isn’t the case. Second, around half the world is colored in similar shades of red-orange, which really distorts the results at first glance. Saudi Arabia and Uzbekistan are separated by a full 25 points, one-quarter of the entire scale, and it’s hard to tell their colors apart on the map.3

I’m not sure if this is just awful graphic design, but I get the feeling that there might be political or financial concerns at play. Does an organization that exists to reveal corruption have incentive to make things look worse than they really are?

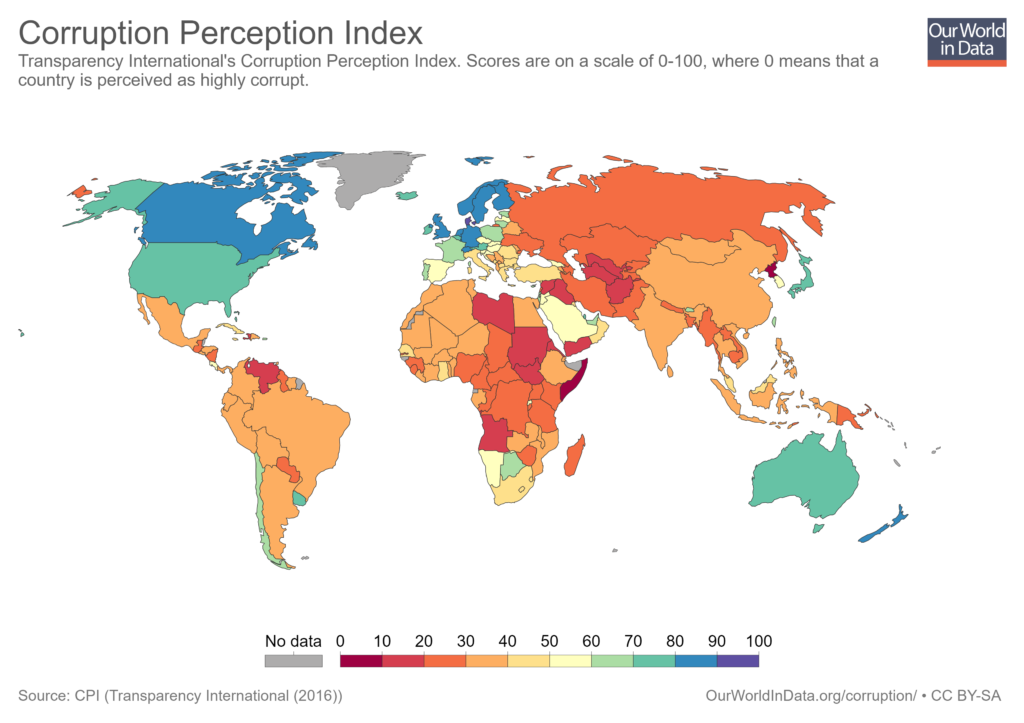

For comparison, here’s a chart made by a different organization using Transparency International’s 2015 data:

Hmm. Looks a bit different, don’t you think? You can actually see variation between countries in Africa, and not surprisingly, Saudi Arabia and Uzbekistan are two radically different colors.

I guess my main point is that shrewd readers must watch for bias and unfounded assumptions in journalism. It’s a crappy situation due in part to the way in which the Internet gives huge incentive to be first rather than to be correct. It’s also a testament to the politically-charged times in which we live, where political alignment clouds judgment and causes people to make bad mistakes.

If you liked this article, be sure to check out:

16 Psyche and the End of the World

Net Neutrality

Tommy Robinson is in Jail

- Looking at the author’s credentials suggests that he should know better. He admits that corruption within the U.S. isn’t a problem, and then casts the case for staying in as an opportunity to correct a lack of U.S. leadership, a tiresome liberal talking point that has little to do with the topic at hand.

- The article really frustrates me because it ranks highly in Google searches on the subject, but it’s hard to not suspect that the author willfully misunderstands the situation

- Bonus points if you know where Uzbekistan is