A while back I wrote a post about the price of pharmaceuticals, and how the US appears to be subsidizing the rest of the world. There was something regarding pharmaceutical advertising I stumbled across at the time that concerned me, but I didn’t know quite what to do with it.

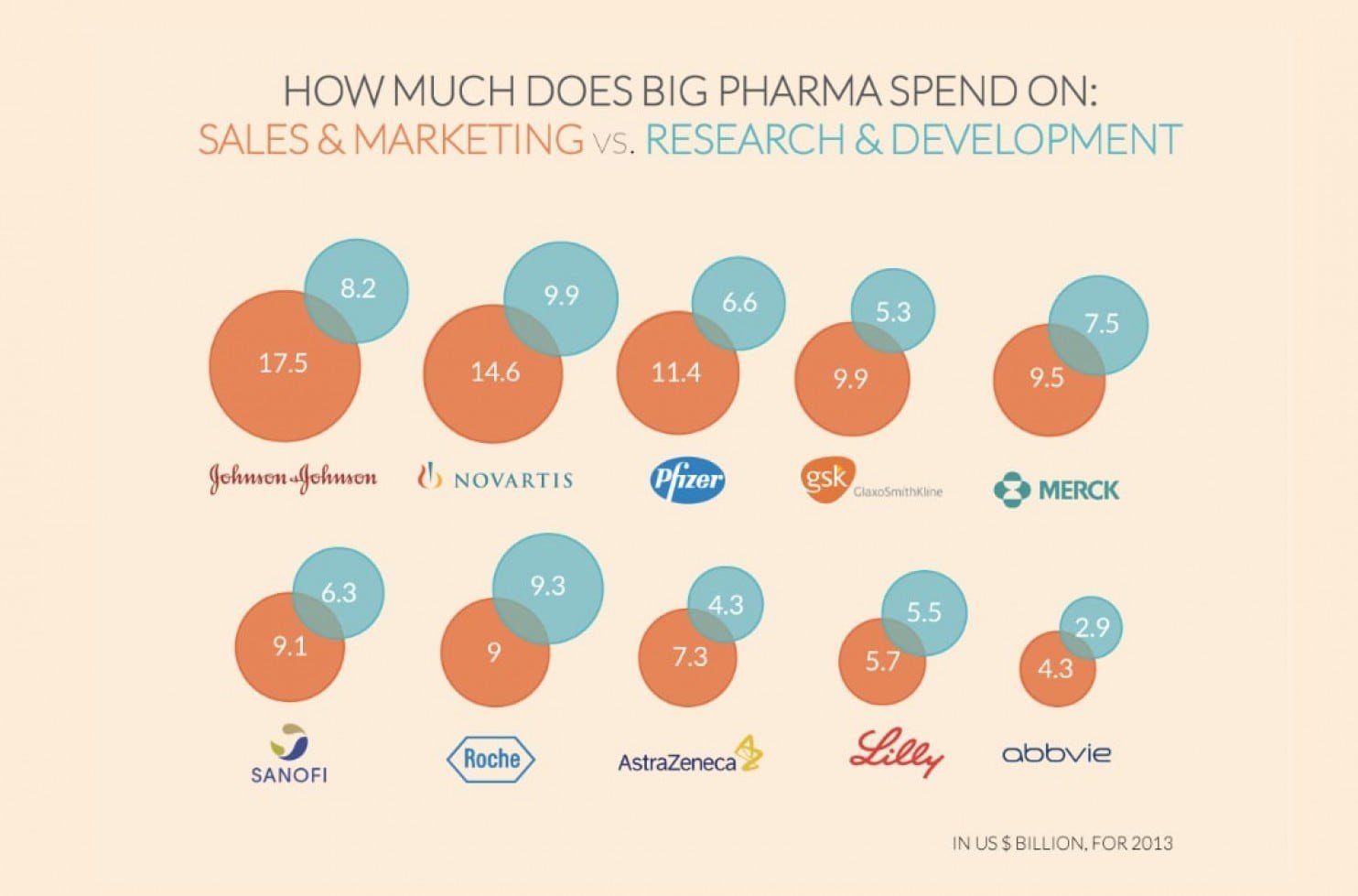

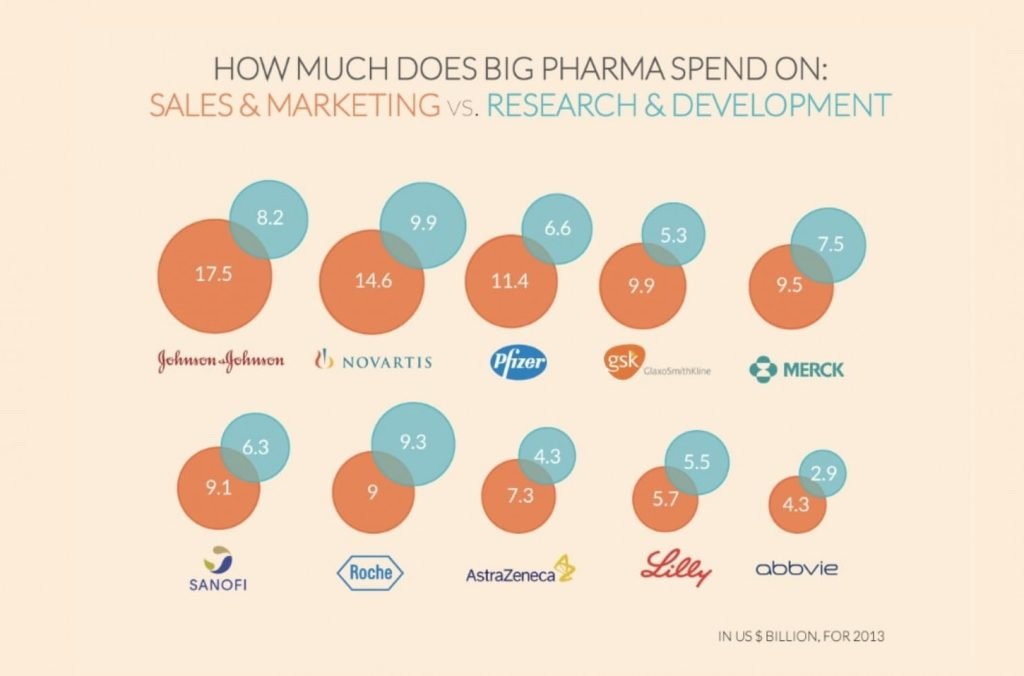

Apparently, most drug companies spend more on pharmaceutical advertising than they do on research and development. And it’s not even close:

Source: https://www.washingtonpost.com/news/wonk/wp/2015/02/11/big-pharmaceutical-companies-are-spending-far-more-on-marketing-than-research/?noredirect=on&utm_term=.8b5fa896fdcd

If this is true, then there’s something worth talking about here. Is it possible that scaling back on advertising could lead to cheaper drugs?

However, one of the first things I noticed on the chart was that the first company listed was Johnson & Johnson. What’s notable about seeing that company on the list is that it makes things that aren’t pharmaceuticals.

So, I couldn’t help but wonder if the R&D and advertising spending was for the company as a whole or just the pharmaceutical division.

I believe I’ve tracked them down to their original source, a 2014 article by the BBC, that provides no link to where the data was found, but instead just writes “Source: GlobalData.”

There’s a reason there’s no link. GlobalData is a research firm that appears to charge hundreds and sometimes thousands of dollars for access to its research pieces.

That organization also appears to remove old data from its website, which means that the source I’m looking for may no longer exist. Even if I found it, I couldn’t afford it.

Since I can’t look at the raw numbers, I can’t tell you with absolute confidence that the numbers in questions are both accurate and in proper context.

Even if we have to take those numbers with a grain of salt, there are still some useful questions we can ask about the nature of pharmaceutical advertising.

Like, does it work?

Oh yeah.

A widely-cited study from 2001 attempted to answer this question by figuring out the return on investment for different types of pharmaceutical advertising.

The best kind of advertising turned out to be that which was directed at doctors.

Ads placed in medical journals provided an ROI of between $2.22 and $6.86, with an average of $5.00.

Spending on physician meetings and events created an average ROI of $3.56

Detailing, or 1-on-1 interactions or visits to small groups of doctors by company representatives, provided an ROI of between $1.27 and $10.29. The average was $1.72.

The final, and most controversial today, ad type is Direct-to-Consumer, which provided an average ROI of $.19, with a range of $0 to $1.37.1 Clearly, this was the least effective type.

What these raw numbers from almost 20 years ago tell us is that advertising can be very, very effective for pharmaceutical companies, but also that it’s way more profitable for those companies to advertise to doctors.

We actually see this play out in real life.

A 2012 study reveals that pharmaceutical companies spend around $3 billion on advertising directly to consumers. Which sounds like a lot, until I tell you that they spend $24 billion on advertising to doctors. That’s 8 times as much. If accurate, it suggests that the research from 2001 holds up, since the vast majority of their spending is focused on channels with a higher return on investment.

However, these numbers are just for spending in the United States. Total spending worldwide was estimated for the year 2013 to be about $85 billion.

Comparing that number to the graphic presented at the beginning of this piece creates a problem.

If we add up the advertising numbers presented in the graphic, which ostensibly accounts for only the top-10 companies in the world, we come up with $98.3 billion. And that’s not even taking the smaller companies not in the top-10 into account.

That’s a difference of more than $13 billion, or almost 16%. That’s quite significant and gives us cause to doubt the first numbers. Why do they seem so far off the mark?

At least part of the problem may stem from the fact that advertising spending is often lumped into a larger category known as SG&A, which stands for Selling, General, and Administrative Expenses. While Research and Development gets its own line in financial reports, “SG&A is a sort of catch-all category that does include sales and marketing expenses, including sales salaries, support . . . legal and accounting fees, rent and utilities.”

FiercePharma, an online journal focused on the medical industry, estimates that $31 billion in total was spent on advertising in 2010 when the parts of SG&A that aren’t ad-related are factored out, while $67 billion was spent on research.

At the end of the day, I’m not sure I can make a definitive claim here. There are just too many conflicting numbers.

But, there’s a line towards the end of that FiercePharma article that really jumped out at me. The author suggests that “the whole debate [concerning how much is spent on advertising] seems to suggest that people are uncomfortable with the very idea of drugmaking as a for-profit business.”

Which makes a certain amount of sense.

There are a lot of things you can live without in life, but life isn’t one of them.

I guess it feels like we might not have to spend as much on drugs if the companies didn’t advertise. The problem with that stance is that pharmaceutical advertising is very profitable. If the companies didn’t advertise, they wouldn’t sell as much medicine. And if they didn’t sell as much, prices would likely rise.

I’m not trying to say that prices are fine or that the industry has no ethical problems when it comes to pricing its medicine, just maybe that no matter what the correct advertising numbers are, we might be focusing on the wrong thing in this particular debate.