Maybe you live under a rock and this your first time hearing that Donald Trump has pulled out of the nuclear deal with Iran. If so, surprise!

But, this probably isn’t a surprise to you. Trump has been saying he’s going to do it for a long time, and given his recent success with North Korea it makes sense that he’s moving on this now.

I’ve been doing a lot of research, trying to figure out if pulling out of the agreement, known as the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action, is a good idea or not.

I hate to say this, but my conclusion is that it depends on whether you think Iran is a good actor or a bad actor. To put it another way, do you believe Iran is trustworthy and that it will become a responsible member of the international community?

To the best of my ability, I’m going to try to give you a description of both scenarios.

Iran is a Good Actor

Look, at one point Iran may have been pursuing nukes. But, the world came together and levied sanctions through the United Nations. They may not like it, but Iran has realized that they need trade more than they need nukes. The cost of complying with the JCPOA is relatively low. And with looming social issues at home, Iran needs the economy back on track.

On the flip side, the cost of not complying with the JCPOA is massive. In a worst-case scenario, Iran gets caught clandestinely building nukes and the UN sanctions a peacekeeping mission to enforce compliance, which would likely result in the dissolution of the Iranian government.

If you take a look at the JCPOA, you can see that it does a lot to prevent Iran from developing nukes. It reduces the capacity to produce military-grade plutonium, it reduces the amount of plutonium that Iran can keep on hand, and it shuts down a lot of enrichment equipment, period. It also allows for the International Atomic Energy Agency to inspect nuclear sites to ensure compliance.

Because the penalty for defying the agreement is so high, it’s hard to imagine Iran doing such. And furthermore, it paves the way for peaceful resolutions of conflicts between countries in the future. If it works, this agreement would serve as an excellent blueprint for creating a safer world.

Iran is a Bad Actor

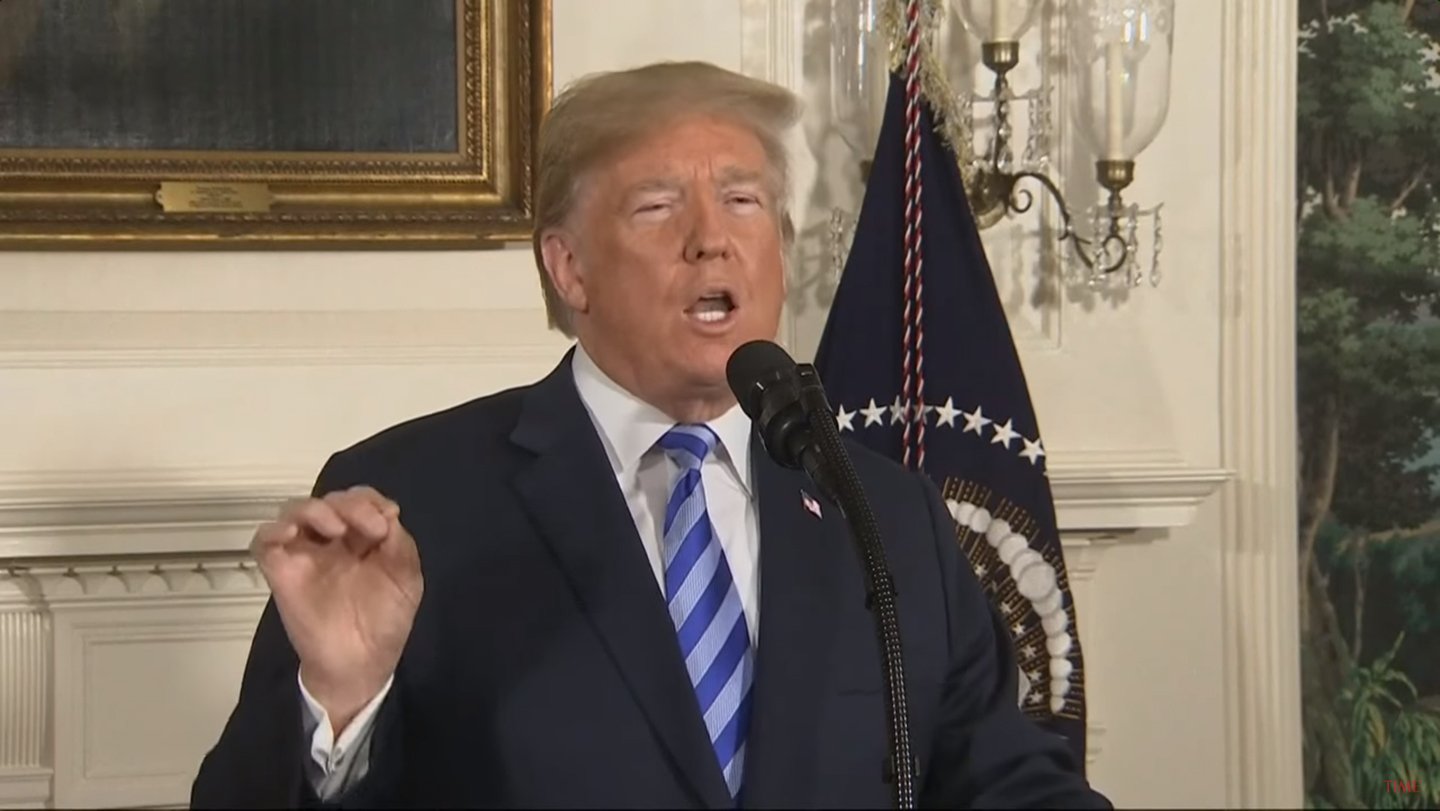

In his speech announcing that he was ending U.S. involvement in the JCPOA, President Trump pointed out that Iran “supports terrorist proxies and militias such as Hezbollah, Hamas, the Taliban and Al Qaeda.” Much of this support is clandestine. There’s also the fact that Iran was running a clandestine nuclear program for a number of years.

So, maybe it would be wrong to put our complete trust in them. It makes a lot of sense for the UN to demand that Iran open up every possible nuclear test site/centrifuge/what have you to inspection by the IAEA. The JCPOA only requires access to a limited number of sites. In recent years the U.S. has asked for the IAEA to have access to a couple of Iran’s military bases, under suspicion of nuclear work being done there.

Iran has denied access to these bases, which doesn’t prove that there is nuclear work taking place, but does indicate that they have a less-than-complete commitment to being open and forthright.

There’s another big problem with the JCPOA: it might not stop Iran from building nukes.

You might ask, “how does a treaty designed to prevent Iran from building nukes not stop Iran from buildings nukes?”

And the answer is that, for whatever reason, the negotiators focused more on slowing Iran down than stopping it completely. It seems fair to me that the international community could demand that a country that ran a secretive nuclear weapon program give up its enrichment altogether. If it wants to have nuclear power plants, great, but it must import all the nuclear material it needs and export the remains. It’s like being on probation.

But, the negotiators allowed Iran to continue refining uranium. They did require that the roughly 20,000 centrifuges be reduced to around 5,000, and according to Vox, those “must be among the oldest and least useful ones.” What concerns me about the other 15,000 is that they weren’t required to be destroyed or dismantled, rather, stored or in some cases merely kept idle.

Which means that all that’s standing between Iran and full capacity enrichment is pulling the machines out of storage or just turning them back on. Vox estimates that “[b]efore the deal, Iran could likely make a nuclear bomb within two or three months if it decided to. But after the accord, it would take Iran about a year to make that weapon.”

That’s not terribly reassuring.

And, then there’s the missile problem. Iran remains dedicated to developing intercontinental ballistic missiles, which are famed for carrying nuclear payloads. Iran’s missile program was not addressed in the JCPOA, which means that even if nuclear development has to be put on hold, missile development can continue.

There’s also the time-limit problem: “[t]he restrictions on Iran’s centrifuges disappear after 10 years, and the limits on uranium enrichment go away five years after that.” In some ways, the JCPOA just punts the problem of Iranian nukes down the line. The world will likely have to start anew when the JCPOA expires.

In theory, the deal might have done what was expected of it. It’s entirely possible that Iran would have stuck to both the letter and the spirit of the agreement and given up its nuclear ambitions altogether. Or, it’s possible that this agreement would have done very little to slow the rogue regime down. We won’t know at this point, because Trump has left the deal. According to CNN, “Iran’s President Hassan Rouhani said Tuesday that he was [already] ordering the country’s atomic industry to be ready to restart industrial-scale enrichment of uranium, but other officials indicated Iran intends to continue sticking with the deal.”

So, I’ll repeat the question that I began with. Is Iran a good actor or a bad actor?1

- There was a quote from Trump’s speech that I especially liked, and I haven’t seen any reporting on it. Here it is:

“Finally, I want to deliver a message to the long-suffering people of Iran.

The people of America stand with you.

It has now been almost 40 years since this dictatorship seized power and took a proud nation hostage. Most of Iran’s 80 million citizens have sadly never known an Iran that prospered in peace with its neighbors and commanded the admiration of the world.

But the future of Iran belongs to its people. They are the rightful heirs to a rich culture and an ancient land, and they deserve a nation that does justice to their dreams, honor to their history and glory to God.”