Just what is a genre?

After discovering, once again, that online dictionaries are almost entirely useless for answering a question with any degree of subtlety, I found myself returning to two old favorites of mine.

In A New Handbook of Literary Terms, David Mikics writes that “The word genre means kind: a genre is a kind of literature. Among the more familiar genres are epic, romance, comedy, tragedy, melodrama, lyric, satire, and elegy.” In A Handbook to Literature, William Harmon and Hugh Holman say that genre is “[u]sed to designate the types or categories into which literary works are grouped according to form, technique, or, sometimes, subject matter . . . [t]he traditional genres includes tragedy, comedy, epic, lyric, pastoral. Today a division of literature in genres would also include novel, short story, essay, television play, and motion picture[s].”

In short, we’ve got a problem.

When the experts can’t clearly define the word or disagree on what the “classical” list of genres should be, then there’s a problem with both vagueness and specificity.

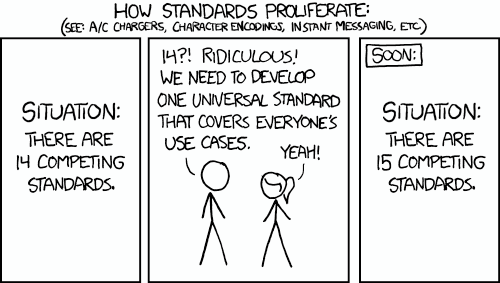

What we need is to understand what we mean when we say the word genre. We need a standard, so to speak. Which reminds me of this comic:

Source: https://xkcd.com/927/

In my defense, I think there isn’t a standard and that every time the word is used people either have to clarify what they mean when they say it or leave it to the reader to interpret what it means.

Let’s start with a short list of genres: adventure, mystery, romance, science fiction, fantasy, western.

The weird thing is that while all could be and are considered genres, they seem to operate differently. Adventure, mystery, and romance all seem to be talking about the kind of story that is taking place, giving you an idea of the kinds of events that will happen. You could change the setting, but as long as you kept the major plot points intact these stories would still be adventures, mysteries, and romances.

And then there’s science fiction and fantasy, where you get a much stronger idea about setting than you do about story. Star Wars, Alien, and Back to the Future tell radically different stories, but all get lumped into the realm of science fiction because they have transformative technological elements.

And then there’s the western, which seems to tell you something about both the story and setting. You’d be hard-pressed to find a western set in modern New York City, as would you be to find one that was about the subtle complexities in the life of a housewife.

How can it be that these words operate so differently, but get lumped under the term genre?

I believe that the source of confusion lies in the fact that we’re trying to do three distinct things with the word genre.

The first thing we’re trying to do is tell you what the form of the story is. For instance, it might be an epic, a novel, a short story, a movie, flash fiction, a lyric poem, or a freeform poem. I think may have been closest to what was meant when the word genre was originally used. If you look back at the lists of genres those authors provided above, you’ll notice that that seems to constitute most of the terms that get used.

The second thing we’re trying to establish is what the plot is going to be like. Adventure, romance, horror, comedy (in the modern sense of the word) would all fall into this category. I think the modern usage of the term genre is closest to this meaning, which is why the terms science fiction and fantasy can be so confusing, as they don’t really tell you much about that the plot is going to be like.

Instead, they seem to tell you something that is closer to the third thing we’re trying to tell you when we say genre, that is, what the setting is. Science fiction and fantasy are two common terms that fall into this category. Something set in the modern world with no fantastical elements might be described as realistic, while something set in the past with no fantastical elements might be described as having a historical setting.

I’ve developed this into a three-part system that I think is rather nifty, as it eliminates a lot of ambiguity. It works like this.

A book’s genre is written like this: setting – plot – form.

Let me show you how nice this can be.

Alien is a science fiction, horror, movie.

Star Wars is a science fiction, epic, movie.

Back to the Future is a science fiction, adventure, movie.

That removes a lot of ambiguity, even though all three are science-fiction movies.

But we can go further. It’s weird to call J.R.R. Tolkien’s The Lord of the Rings books fantasy if we’re also calling Terry Pratchett’s Discworld books fantasy. One is dark and epic, while the other is more shallow but funny as all get out.

Consequently, The Lord of the Rings books are fantasy, epic, novels, and the Discworld books are fantasy, comedy-adventure,1 novels.

To be clear, some of these terms can appear in different positions.

For instance, you could have a western, western, novel, a novel that has both a plot and a setting that are western.

Additionally, you can add adjectives to the different terms to be more specific, such as “hard” science fiction, or children’s adventure, or British short story.

Also, you can sub in terms that would originally have been labeled subgenres. The TV show Firefly might then be classified as a science fiction, space western, TV show. The Lord of the Rings could more specifically be classified as high fantasy, epic, novels. Blade Runner is a science fiction, neo-noir crime, movie. The book it is based upon, Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep, is a post-apocalyptic science fiction, crime thriller, novel. The Mad Max movies could be defined as post-apocalyptic, action (car racing), movies.

What I think is best about this system is that it allows for a great deal of specificity, but also when applied, it allows for more detailed comparisons within genre and across genres. Or at least, we’ll be talking past each other less, since our terms will already be defined.

If you liked this article, you might enjoy:

The Limits of Literary Theory

10 Book Recommendations in 100 Words or Less

Hemingway’s Six Words Aren’t a Short Story