How We Got Here: Macedonia

Welcome to the next piece in the “How We Got Here” Series. Last time we took a look at how things in Israel and Palestine got so bad.

Today, we’re going to get to the bottom of why Greece has kept the Republic of Macedonia out of the EU. At first glance, it seems weird that Greece would be sufficiently threatened by a country of about 1/5th the size and with 1/5th of the population, and yet Greece has threatened to use its veto power to prevent Macedonia from improving its international standing.

So, what’s going on?

Well, in order to understand that, we’re going to have to go way back.

Like, Alexander the Great back.

Just kidding.

Just kidding.

I do want to point out that Alexander the Great was Macedonian, and some of his first conquests were other Greek cities to the south of Macedonia.

Here’s where Macedonia, the region, is overlaid onto a modern map:

Our story today really begins in the mid-14th century, when the Ottoman Empire bypassed the weakening Byzantine Empire and conquered much of the Balkans. By the mid-15th century, the Ottomans solidified their control over the Balkans, and also finished off the weakened Byzantine Empire and claimed Greece for themselves.

These areas remained under Byzantine control until the 19th century.

The Greeks launched a revolt in 1821 and gained formal independence in 1829.

Bulgaria was released as its own country as a result of a treaty between Russia and the Ottoman Empire in 1878.

Montenegro and Serbia, in a loose alliance, took advantage of the conflict between the Russians and the Ottomans and launched their own revolt and were able to leverage the advance of the Russian army elsewhere into a treaty that granted them formal independence and territorial concessions in the same year.

Over the next few decades these new countries, driven by nationalistic fervor, were able to take further small chunks of land from the Ottomans. At least part of their success can be attributed to the desire for self-determination after centuries of foreign rule. It’s also worth noting that the ethnicity played a large role in this. The areas that these new counties successfully captured tended to have residents of the same ethnicity as the rest of the country. They were in theory, if not necessarily in practice, restoring their countries to the borders they held prior to the Ottoman conquest centuries before.

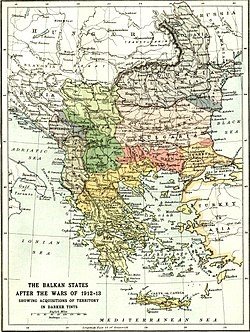

This leads us to the year 1912. This map is in German, but I think you should still be able to get a good idea of what the region looked like at the time.

Greece, Bulgaria, Serbia, and Montenegro signed a series of treaties that created the “Balkan League.” Originally, the alliance was between Serbia and Bulgaria, and brokered by the Russians with the intent of being aimed at Austria-Hungary, but the two countries secretly decided to target the Ottoman Empire and eventually added the other two countries to their planning.

Against the odds, this plan ended up working. The four countries declared war in 1912, and the Ottomans weren’t able to put up much of a fight. This was partly due to how disorganized the Empire had become, but was also due to the fact that the majority of the Ottoman army and recruitable population was on the east side of the Bosporus Strait.

The Greek navy won a few significant victories, which meant that the Ottomans were unable to move the bulk of their armies west to where the battles were being fought.

The war resulted in total victory for the European countries.

Serbia, which had old claims on Macedonia was forced by Bulgaria to give them up in exchange for parts of Albania that would have provided access to the sea.

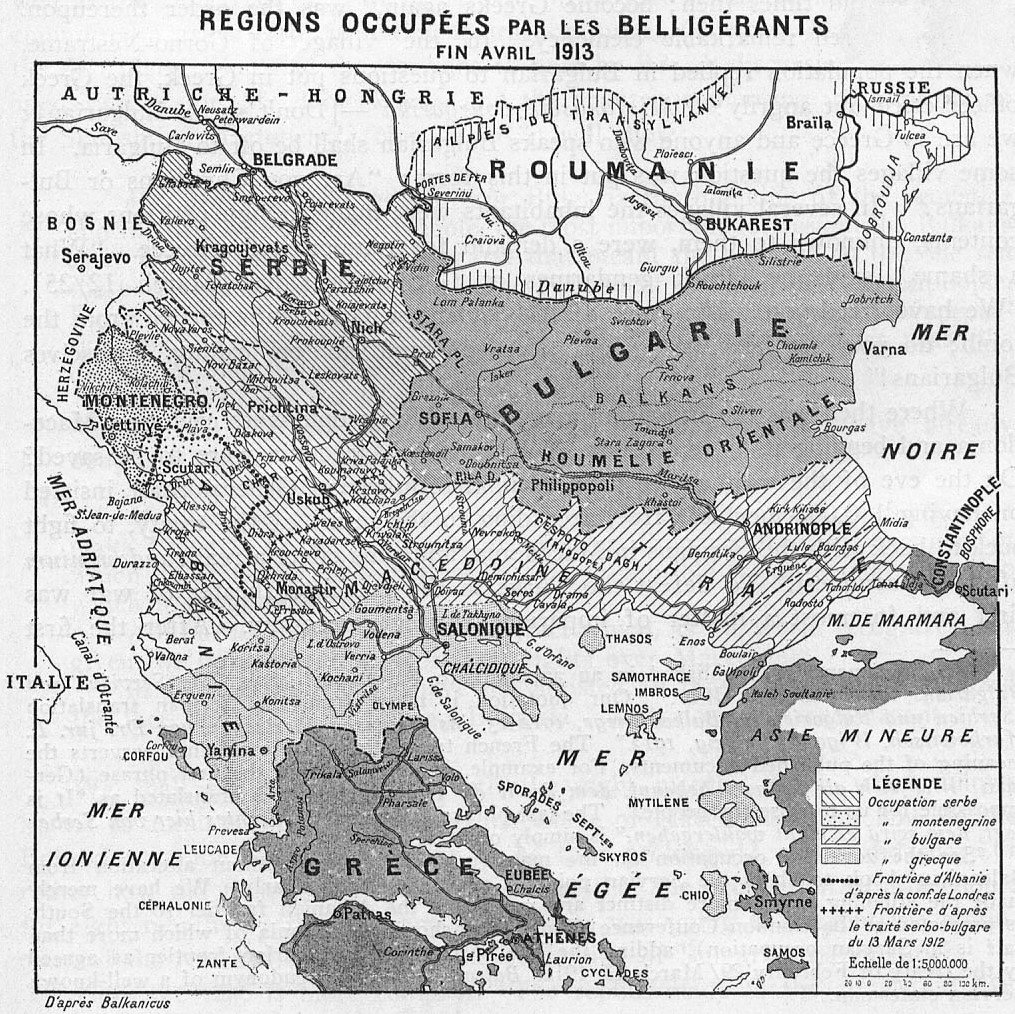

This left the region looking like this:

However, Serbia and Greece decided to ignore provisions of the treaty that would have restricted their territorial expansion and ended up claiming territory that was, in theory, supposed to belong to Bulgaria.

and ended up claiming territory that was, in theory, supposed to belong to Bulgaria.

Bulgaria declared war in 1913, setting off the Second Balkan War, and in one of those moments where truth is stranger than fiction, the countries of Montenegro, Serbia, Romania, and Greece gained the help of the country they had just defeated, the Ottoman Empire, against their former ally, Bulgaria.

Bulgaria lost this war and was forced to give up some of its territorial gains to Greece and return some land to the Ottoman Empire.

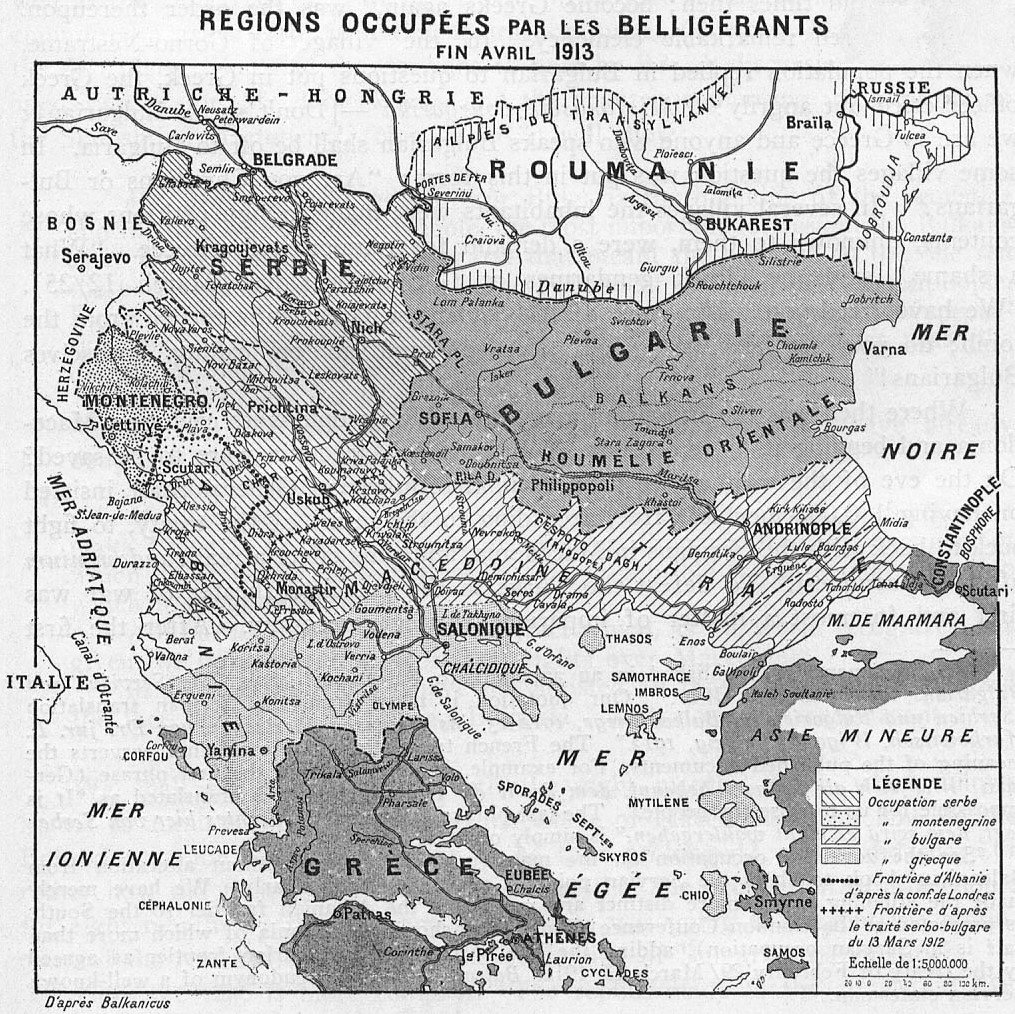

Here’s what the area looked like at the end of the war:

A lot of stuff happened between 1913 and the present, such as both World Wars and the rise and fall of the Soviet Union.

But, what really matters here is the fact that the Republic of Macedonia emerged from the fall of Yugoslavia in 1991.

Today the map looks like this:

As you can see, the Republic of Macedonia is clearly within the geographic region of Macedonia. It’s also pretty clear that there’s a lot of Macedonian territory outside that country as well.

Modern Greece is concerned, perhaps unjustifiably, that its neighbor’s name implies territorial ambition over some of its lands. It would sort of be like thinking that the United States of America had territorial ambitions over the rest of North America.

However, there’s more to this story.

There’s a strong push in the Republic of Macedonia for what is known as “United Macedonia,” which suggests that the country was wrongfully divided back in 1913 at the end of the Second Balkan War, and should rightfully be united.

Elsewhere in the world, this might be an idea constrained to fringe groups.

In the Republic of Macedonia, it’s taken seriously. According to Wikipedia, “The United Macedonia concept is still found among official sources in the Republic, and taught in schools through school textbooks and through other governmental publications.”

Knowing that, we can understand why Greece might be concerned. Probably not that concerned, because Greece would probably win any war, but concerned enough that they might demand a name change that would cool down territorial ambitions before allowing the country to join the EU.

On June 20th, the parliament formally ratified an agreement with Greece that would change the name from the Republic of Macedonia to the Republic of North Macedonia. Sounds silly at first, but we can see how it makes a big difference.

However, it is likely to be vetoed by the president, whose party is descended from a Macedonian rebel organization that dates back to the 19th century, and derives its support largely from “ethnic Macedonians,” who might like to see a United Macedonia.

Because of this, there’s no easy end to the conflict in sight.