I bet I can prove to you that language doesn’t work the way you think it works. In fact, I bet I can prove that your teacher taught you well, but incompletely, to the point where you, like most people, misunderstand how language works.

For instance, I can prove to you that the word “ain’t” is grammatically correct.

Answer these questions for me:

What’s the third-person negative form of the phrase, “he is”?

Well, that would be “he is not” or “he isn’t”

What’s the second-person negative form of the phrase “you are”?

That’s “you are not” or “you aren’t.”

How about the first person?

“I am” becomes “I am not” becomes “I am not”

If the pattern is correct, doesn’t “ain’t” follow the rule?

Isn’t . . . aren’t . . . ain’t.

If you’re like me, you might look at that pattern and suggest that “amn’t” works better than “ain’t,” in terms of following the pattern, but it’s hard to deny that there should be something there.

I adapted this exercise from Understanding English Grammar by Martha Kolln and Robert Funk. They use it in the introduction to their book, and I think it’s a good way of getting people to start thinking about not just the “what” of language, but also the “why.”

For instance, why is it that “ain’t” is wrong, but “isn’t” and “aren’t” correct?

Here’s what they say on the topic:

“You may have assumed that pronouncements about ain’t have something to do with incorrect or ungrammatical English—but they don’t. The word itself, the contraction of am not, is produced by an internal rule, the same rule that gives us aren’t and isn’t. Any negative bias you may have against ain’t is strictly a matter of linguistic etiquette . . . Written texts from the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries show that ain’t was once part of conversational English of educated people in England and America. It was sometime during the nineteenth century that the word became stigmatized for public speech and marked a speaker as uneducated or ignorant.”

That’s something else, isn’t it?

Even as I write this piece in Word, every example of “ain’t” is underlined in red, while “isn’t” gets away scot-free.1

Kolln and Funk suggest that this phenomenon is representative of the socially-constructed nature of language. That’s not a bad observation, by any means, but I think we can take it a step further.

Not only is language socially-constructed, but the rules, as they’re found in the textbook, or as given to you by your teacher, aren’t authoritative.

To misquote one of the world’s funniest gameshows:

“The rules are made up, and they also don’t matter.”

Maybe you’re convinced at this point, or maybe you’re not, and that’s okay.

We can come at this idea from a completely different angle.

Let’s talk cuneiform.

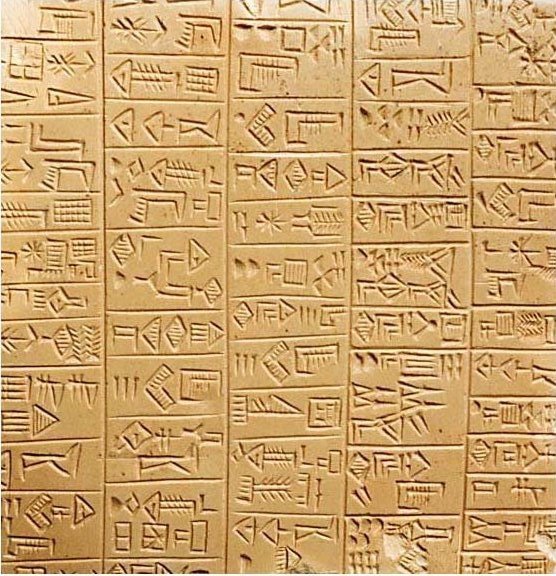

Cuneiform is a contender for “first/earliest system of writing.” It was developed by the Sumerian civilization, and was based on pictographs, or symbols that represent words, often by looking like the object or concept they represent. They looked something like this:

What’s really interesting about cuneiform is that in its earliest form it was an accounting language, “evidently lists or ledgers of commodities identified by drawings of the objects and accompanied by numerals and personal names.” Its original purpose was to record economic transactions, which tells us two interesting things.

First, economic transactions were taking place.

Second, people were able to communicate to each other verbally in a way that was complex enough to perform economic transactions, and was likely more complex, as cuneiform evolved over time in order to be able to record more complicated thoughts.

There were no Sumerian grammar textbooks, so how did they learn to speak it?

Well, if we go far enough back, there were just grunts and sounds that came to be mutually understood as having specific meanings by members of a community. These systems became more complex over time. Soon, they were rich enough to be called language.

But, again, how did they learn to speak it?

Well, like you did. You heard your parents talking, and over time you realized that certain words had certain meanings and go in certain orders. You don’t need a grammar textbook to teach you that.

Think about it this way: verbal language predated the printing press. It predated books, scrolls, paper, or any means of representing language in the written form.

The grammar rules come after the spoken language.

This means that generally speaking, there’s no rational reason why anything in a language is the way that it is. There’s no “higher linguistic power” that determines if a word, phrase, or spelling is right or wrong.

What makes it right is that it was agreed upon.

This presents a problem in teaching language, however. Grammar texts tend to approach the topic like they are prescriptive: telling you how things ought to be.

Instead, what they’re actually doing is being descriptive, or telling you what people have generally agreed on. The “rules” aren’t rules at all. They’re a series of connected and renegotiable agreements.

The problem is that since the rise of the printing press and of grammar handbooks, we’ve come to think of language as static. In that mindset, things shift from being “typical or atypical” to being “right or wrong.”

Furthermore, sometimes people write influential grammar textbooks, and their pet peeves become rules, even if there’s no reason for it. Other times the language evolves, but the written language doesn’t follow suit.

For instance, in Middle English, the word “Knight” was a three-syllable word, pronounced with a hard K. Today, as you know, it’s pronounced the same as the word “night.” We choice we apparently made was to keep the spelling so that it was distinct on the page, even it meant that the written language word wouldn’t correspond as well to the spoken one.

Similar words like “knee” and “knife” have kept their “k” even though there would be no confusion if it were to be dropped.

It’s so weird that we teach language in school primarily based on the static written-form. When we’re talking to each other, there’s no spelling or punctuation. As I argued before, there aren’t even authoritative rules.

While our written language is standardized, perhaps we have gone too far. In too many circumstances it fails to accurately represent the way in which we speak. That’s important, since that’s the more authoritative version of the language.

As if we needed another reason to hate Grammar Nazis.

If you liked this article, be sure to check out:

The Livonian Crusades

Characterizing the Intellectual Dark Web

How We Got Here: Macedonia