Author’s note: This is part 3 of a series. Part 1 can be found here, and part 2 here. This piece is roughly equal to 3 of my normal pieces, so the next post will come on Thursday.

How do we read the Titanic disaster?

It was a tragedy, surely. A lot of people died unnecessary and brutal deaths.

But there’s more to it than that.

We’ve learned since then that there were a lot of design flaws that were major players in the ship’s sinking. The riveted plates likely buckled and came loose when struck by the iceberg. The bulkheads weren’t watertight, meaning that a small number of breached ones ended up quickly flooding the ship. There weren’t enough lifeboats, and priority access to those was given to people with money. The Titanic had been warned of icebergs and didn’t slow down.

Yes, all of these things were problems on one ship. But many ships, maybe even a majority of ships, had the same structural and design flaws and were crewed by people with a flawed emergency response plan.

What happened on one ship had ramifications for the whole shipping industry because it shared common features with much of it.

I say all of this because I can hear the objections to what I’m about to write already. If I’m being honest, I probably harbor them myself.

“It’s just one article.”

And it is, just as the Titanic was just one ship. But, I think this article shares many common features with a great number of articles that are published today, whether it be through newspapers, websites or cable TV.

The article is “Museum not Place for Lee Statue,” by Robert Wilonsky, published on the front page of the Metro & State section of the Dallas Morning News.

You really need to read that article before continuing on with mine.

Read it?

Good.

Like you, I felt there was something I had to do before I responded to this article. I needed to reach out to Wilonsky and ask a couple of questions. I emailed him last week and got no response. I also thought that it would be good to visit the museum in person. There was stuff in the article that my gut said might not be true, but I wanted to see it in person to verify that feeling. I’m glad I did because I learned a pair of things that have brought a lot of clarity to this article.

I could easily nitpick Wilonsky’s article, but I’m going to restrain myself to only talking about things which are a big deal and might have ramifications nationwide.

Wilonsky starts the article by setting up the situation, which is that the city council is going to vote to either give a controversial General Lee statue to a museum or sell it.

Things don’t get weird right away, but when they do, they get really weird.

Take these lines:

“[T]he museum ‘has purposely displayed artifacts equally.’ Which I guess is mostly true . . . But it’s no more 50-50 than a coin toss with a two-headed quarter. The vestiges of the Texas Confederate Museum tilt the collection southward.”

Now, both of these statements cannot be true.

That’s part of why I went. I wanted to know which was the case.

Here’s a map of the museum. I’ve drawn labels on the major section:

The main gallery was just as described: split down the middle, with artifacts from the North and South on opposite sides. Here’s a picture I took of that space:

Each section was perfectly mirrored on the other side. For instance, if a case had Confederate infantry uniforms worn by privates, the case on the opposite side contained Union infantry uniforms worn by privates. It was like this through the entire main section.

Like Wilonsky said, it wasn’t 50/50.

There were more Union artifacts.

Not by a whole lot, but it was maybe 55-45 or 60-40 in favor of the Union. Furthermore, what seemed to me to be the two most valuable artifacts were both from the North. This museum has a field coat worn by General Grant, possibly at Appomattox, and one of Grant’s ceremonial swords, a gift from the state of Kentucky.

So, both by likely value and by raw number, there were more Union artifacts. It never felt overwhelming, but the disparity was there. It just happens to be the dead opposite of what Wilonsky claims.

However, that’s just the main exhibit. Wilonsky’s right that “the vestiges of the Texas Confederate Museum tilt the collection southward.”

I’ve labeled those vestiges in green on the map above. These donated collections appear to have been given to the museum in large chunks. Much of these donated materials have tenuous connections to the Civil War, seemingly qualified by being owned by someone connected to that conflict. For instance, a piano bought by Jefferson Davis for his daughter makes the list, as does a fireproof safe owned by the Confederate government.

It seems odd to me to lump it in with the main collection. Everything in the main collection is something that was worn or used by a soldier, and not everything in the donated collection is. I think keeping them apart was a wise move from the museum. They’re not meant to be understood in context of each other, something which Wilonsky fails to grasp, or understands but ignores in his reporting.

I labeled the flag room because it was large, and I thought you might have questions about it. It’s just wall space for four confirmed and one likely unit flags from the State of Texas. Logical thing to have for the Texas Civil War Museum. The main exhibit contains an alcove with a roughly equal number of Confederate and Union flags from other states.

And then there’s the Victorian Dress Collection, which is cool, but not terribly relevant to this article. But the way I see it, it’s one of the three collections housed under the same roof. Judging the main collection by the dress collection would be just as much a mistake as judging the donated collection in light of the main. They’re different rodeos.

But, back to Wilonsky’s article.

“The vestiges of the Texas Confederate Museum tilt the collection southward. So, too, does the film playing in the theater . . . in which the ‘sectional crisis’ is presented almost entirely as a tussle over states’ rights.”

I don’t have a transcript of the video or a copy of it, but this characterization strikes me as inaccurate. I don’t think the video explored the causes of the war at all. So, it certainly didn’t say it was slavery, but it also didn’t say anything about state’s right either. Of course, this is as memory serves.

Should the museum have a stronger position on the causes of the war?

I don’t know. Sometimes we get so tangled up in the “why” that we lose sight of the “what.” It’s also something that’s covered extensively in school.

For some reason, Wilonsky feels the need to attack the museum for its position of near neutrality, which in many cases is academically correct. I don’t see a particular problem with the museum not telling you what to think.

Back to Wilonsky, again.

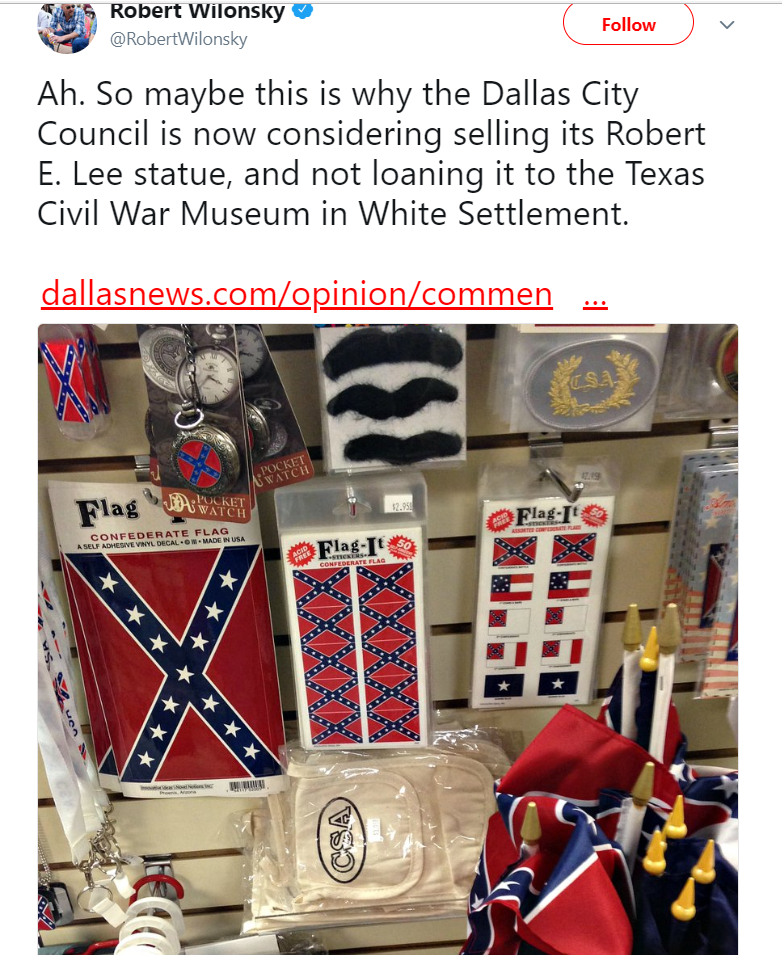

“On my way out, I hit the gift shop, larded with CSA belt buckles and “the ONLY reproduction ever made from General Robert E. Lee’s Dress Sword Belt Plate.”

He goes on further about the gift shop, making it seem like it’s completely full of Confederate stuff. Which, if true, would be a cause for concern.

Here’s a picture of the gift shop he posted to Twitter:

Here’s a picture I took of the same spot:

Sure, there’s some Confederate stuff.

Maybe that offends you.

But, there’s good news. You can walk one aisle over and look at the Union stuff.

The gift shop as a whole isn’t full of Confederate stuff. About a third of it is given over to stuff related to the Victorian dress exhibit, and another quarter to candy. There’s a bunch of research-based books on the civil war. And, as you can see in the photo, the rest of the shop is split pretty evenly between Confederate and Union bric-a-brac.

But, is that what you would have understood if you read Wilonsky’s article or looked at his Twitter feed?

Certainly not.

And I understand that this isn’t part of the article that the Dallas Morning News published. But, it gives us a window into his thought process and approach. It’s not unreasonable to suggest that if he’s willing to be misrepresentative on Twitter, he’s also willing to be misrepresentative in print, at least when it comes to this particular topic.

At this point, I’ve shown you multiple instances where Wilonsky has stretched the truth. I can’t accuse him of outright lying, but I can say that we’re seeing evidence here of a reporter only choosing to report facts that fit a preexisting narrative. Everything Wilonsky puts in his article is designed to make you think something. Namely, that the Lee statue should not go to this particular museum. And funnily enough, he leaves out everything that might go against that argument.

But, there’s a piece of the puzzle that is still missing.

Wilonsky ends the article by writing “Sell the Lee statue, Dallas. Sell it now.”

Which struck me as weird when I first read it. He hasn’t built up to that conclusion. He’s tried to make the case that it shouldn’t go the museum. I hope I’ve given you reason to doubt the integrity of his case on that front.

But what he hasn’t done is make the case that the statue should be sold. I understand the city council is sort of treating it as an “either/or” situation. Either sell the statue or give it to the museum. However, both of these options might be bad.

This is one of the things that I asked Wilonsky about when I reached out to him. What if a white supremacist buys the statue at auction and uses it to create a neo-Nazi shrine?

That’s a plausible outcome of selling the statue, and I would argue that it leaves society worse off.

Which is part of what makes this situation so weird. If the city had left the statue in the park, it could have controlled how it was viewed. In theory, if it started to become a gathering place for white supremacy, it could nip it in the bud by targeting the associated activities, if not the ideology itself.

By giving it to the museum, the city necessarily gives up some of its control. If they sell it, they lose control completely.

Which is why I think that if the statue must be removed from city ground, the Texas Civil War Museum makes a lot of sense. I spoke to a couple of staff members, who indicated that they were happy to have the statue and that they recognized the moral complexity of the object and were happy to put up qualifying signage to that end. They’re disappointed that despite the recommendation of the Mayor’s Task Force that the statue be given to the museum, the city council voted not to do so.

Maybe they read Wilonsky’s article before they voted. I don’t know.

But, why does Wilonsky inexplicably support selling the statue, which has the potential for a worst-case scenario to take place?

The second thing I learned at the museum suddenly made his stance make sense.

One of the workers told me that some people were advocating for a plan by which the Lee statue would be sold and the proceeds from that sale would be used to buy another statue.

The local Fox affiliate reports that city council member Philip Kingston wants the Lee statue to “be sold at auction and the money [used] to fund a memorial for a man named Allen Brooked, a black man who was lynched in front of the Old Red Courthouse in 1910.”

Books’ lynching wasn’t a bright moment in Dallas’ history. I’m not afraid of the dark moments, but if you think back to my first article on Confederate statues, I said the following:

“Surely there’s some kind of middle ground, that remembers without venerating, yet

criticizes within context.”

Given the heavy-handed and unilateral way in which the city council has acted so far, it’s hard to imagine a world in which they commission a statue on a topic such as this that has any nuance. I’m not saying we should ignore what was done to Brooks. It was wrong. But I don’t know that this city council can handle the matter in a way that will promote racial reconciliation.

And, it seems like we haven’t made any progress whatsoever if we sell a racially-divisive statue in order to purchase a racially-divisive statue. Aren’t we just back at square one?

But, let’s leave aside the question of whether that’s the right move.

If we posit for a moment that Wilonsky believes that’s the right move, then we have a good explanation for a lot of the weirdness in the article.

For instance, it explains why he only includes facts that support his narrative that the museum is a bad place for the statue to go. He wants the statue to be sold, and if he can sway public opinion towards that end, he gets what he wants. That’s a clear abuse of his power as a reporter. It’s also incredibly unethical.

To be clear, I don’t have a particular problem with editorials or opinion pieces. I write one nearly every day. And I understand that journalism is increasingly told through the first person. I don’t object to the narrative style in which Wilonsky’s piece is written.

But the basis of a good editorial is the facts. An editorial interprets the facts. And to have a good interpretation, you have to take into account everything that is relevant. Good opinions don’t pick and choose what supports them.

To put it another way, the narrative is built on the facts, instead of choosing the facts to fit the narrative.

Again, to be clear, I’m glad for Wilonsky to write opinion pieces. What I object to is his poor treatment of the facts.

At the start of this article, I talked about the Titanic and suggested that the ship was significant in part because design flaws and crew failure that led to the disaster were spread throughout the shipping ecosystem.

Let’s take this article, written by one journalist for one newspaper, and examine the flaws and failures as though they might apply to all articles, all journalists, and all newspapers, in short, the entire ecosystem.

How many articles are published in non-opinion sections of newspapers that are not news, but rather opinion pieces?

How many opinion pieces are published that are not labeled as such (as happened here)?

Should journalists be allowed to use newspapers as a platform for their personal missions?

At what point in the process should an editor reject or order rewrites for a news piece that has morphed into an opinion piece?

Are the editors unaware of the factual inaccuracies and misrepresentations in the piece?

How many other articles by the same author have the same issue?

How many journalists at the newspaper create articles with similar flaws?

How many newspapers across the country employ journalists that create articles with similar flaws?

Is this an isolated case, or is much of journalism like this at this particular moment in time?

As you can see, it’s still possible that this is an isolated case. Or, at the other extreme, it’s a contagion that plagues all of journalism.

The truth is probably somewhere in the middle. That being said, this is a preventable, fixable problem. It’s why editors exist. I’m really concerned that Wilonsky was able to publish a piece like this, but I’m even more concerned that the editors didn’t put a stop to it.

And, this is just my opinion, but I write pieces like this one all the time in which I point out factual inaccuracies, misrepresentations, and incredibly relevant facts that are just left out of the piece entirely. Most of the time, I don’t even have to do that much research to discover these things. They’re there to be found and the reporters aren’t doing their due diligence.

We can split hairs about how much it happens, but if it happens at all, it happens too much.

Which suggests that there’s either a huge problem with negligence at these newspapers or that there’s at least a tacit acceptance of using the newspaper as a platform to push narratives instead of inform.

We’re told all the time that Americans are poorly-informed. Is it possible that this isn’t because they don’t consume the news anymore, but because the news they consume isn’t news at all, but misrepresentations that fit a narrative?

We’re told all the time that the media is trustworthy. But, what if it isn’t? What if it’s lost its integrity.

I wonder.