A few months ago when I was thinking about starting a blog, one of the first topics I wanted to research was Net Neutrality. Something I’ve realized over the years is that if you hear the same talking points repeatedly from different outlets, there’s probably an interesting story on the other side that isn’t being heard. I guess this article can be used as a way to judge the things I’ll be writing about on this blog: I want to dig into things and find the stories that aren’t being told. Or, sometimes just write a little about the things that interest me, and my friends are tired of hearing about.

That’s the mindset I had when I started looking into Net Neutrality. What was the story that wasn’t being told, namely, the story of the side that wanted to repeal Net Neutrality?

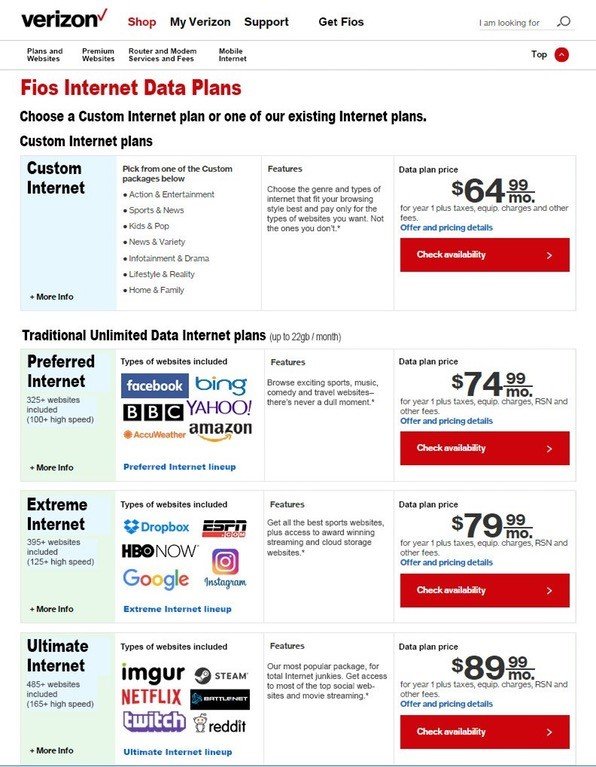

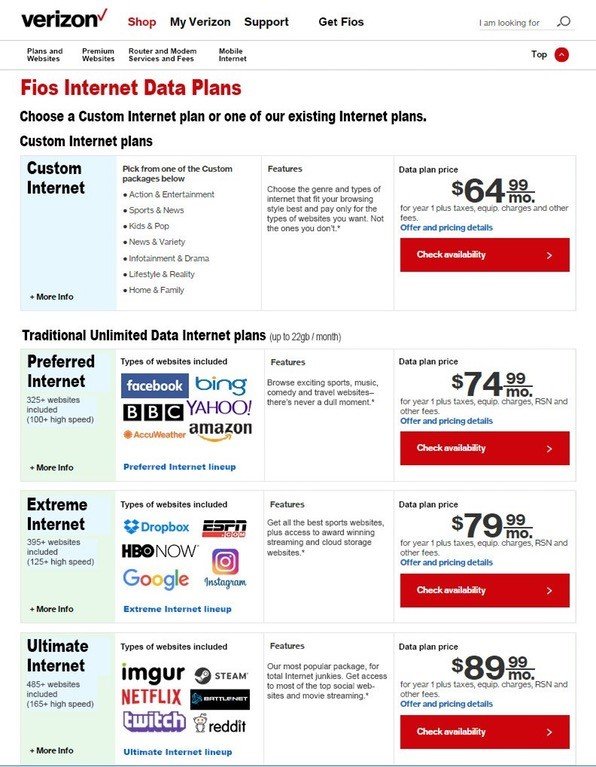

But, first, it would be hard to talk about Net Neutrality without defining it. I don’t want to overdo this, as the topic has been everywhere, but in short, Net Neutrality is the idea that Internet Service Providers (ISPs), the AT&Ts, Comcasts, and Time Warner Cables of the world, should not charge content providers, like Netflix, YouTube, or Reddit more than they would other sites, or ask them to pay more for faster delivery. As a corollary, it means that they cannot censor content they don’t like, or slice up the Internet into chunks and sell access to each chunk in a discrete package.

The latter idea is the genesis of this picture:

It seems to me that this particular package is so unattractive that it would hurt sales more than it helped. With the repeal of Net Neutrality, it is possible that an ISP might cut up the Internet, but why? Most ISPs are public, which means they have an obligation to maximize profit, and the general public has already shown an extreme hatred for this idea. In my opinion, there’s just no market for it. Same goes for the idea that ISPs might slow down the speeds of services or websites that they don’t like. Degrading the quality of your service is a good way to lose customers.

Not to get overly philosophical, but there’s no reason to ban something in a free market if there’s no demand for it. It’s overkill.

Of course, saying Net Neutrality should be repealed because very little would chance is simplistic. A good policy for many things in life is ‘if it ain’t broke, don’t fix it.’ Which, given the fact that Net Neutrality was in place, and not really causing harm, makes it hard to understand why it was suddenly back in the spotlight. Well, the ISPs were obviously in favor, but why? Was it because they want to want to put a package in circulation that no one wants to buy? Something wasn’t adding up.

I have a theory. It’s unsubstantiated, but it makes a lot of sense.

This is all Netflix’s fault.

No, really.

In March of last year, Netflix accounted for 35.2% of downstream traffic in the United States. That’s right; one company is sending more than a third of the traffic on the Internet. That’s a lot.

If you’ve paid any attention at all to Netflix, and internet streaming in general, this information shouldn’t come as a surprise. First, Netflix is insanely popular. Second, they’re sending some of the biggest files on the Internet. There are multiple kinds of things that can be sent over the Internet. Text, or just words on the screen, doesn’t require a lot of data to send. Pictures, on the other hand, take exponentially more data, and video, a series of pictures, plus a sound file, require the most. And then, high-definition video takes exponentially more than standard-definition, as does 4k over high-definition.

In short, Netflix is using a disproportionate amount of the internet, and the companies that provide the connections between that company and its customers are unable to charge that company more, even though they claim the heavy usage causes slowdowns.

I think the behavior we’re seeing out of the ISPs connects their visions of the future Internet to the immediate need to reduce Internet congestion. More and more content will be video, and an increasing amount of that video will be high definition or 4k. And, now that some of the competitors to Netflix, such as Hulu and Amazon Prime Video are starting to gain legs of their own, it stands to reason that ISPs dealing with the most traffic, by volume, that they’ve ever experienced, and they can only expect it to increase in the future.

I’m not necessarily saying that their decision to try and squeeze some more profit out of content providers is a good decision. What I am saying is that it is capitalism at work.

It’s also important to point out that consumers wouldn’t be affected by these charges directly. If Netflix, or a Netflix-like company, is charged more for services by ISPs, they would likely pass those charges along to their customers, likely in a small monthly increase in price. That’s certainly not in your best interest, but, it’s hardly the “censorship of the Internet,” that people are talking about right now.

The solution to this problem seems not to lie in regulation, but in competition. Theoretically, Netflix could adopt tiered prices. Those who used an ISP that charged Netflix more to carry its data would add a surcharge to their monthly bill. Those who were using an ISP that decided not to charge Netflix extra would be unlikely to see an increase in price. Or, Netflix could raise prices across the board. The added pressure might be enough to make ISPs reevaluate their policies.