Late last year, I received for the first and last time since, emails from readers of my blog. One hired me as a freelance writer on a project I greatly enjoyed.

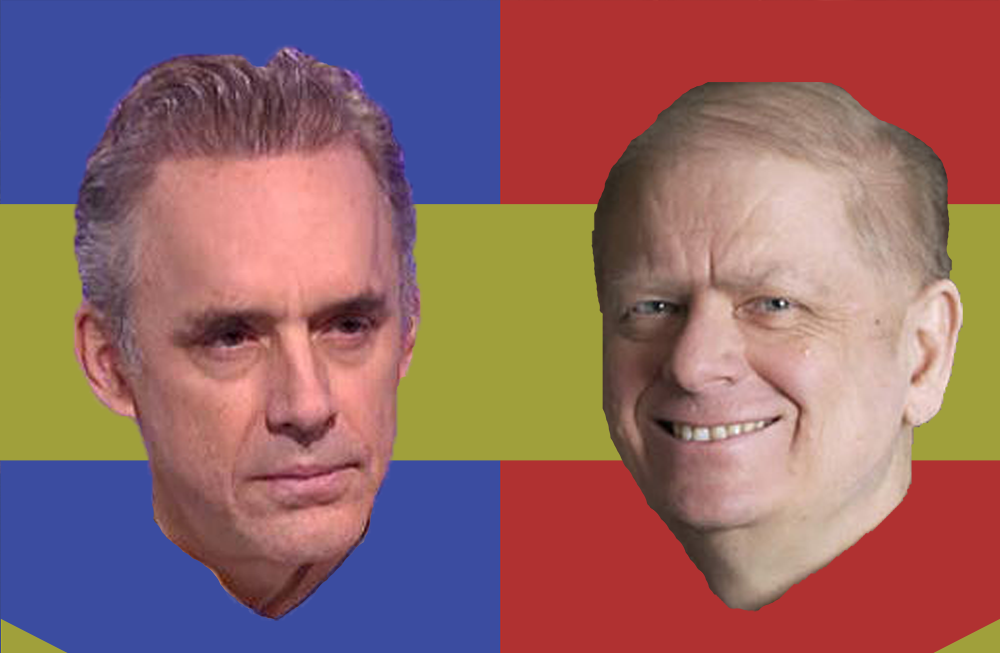

While that was exciting enough on its own, a second person sent me an email, which was a short response to one of my pieces, namely, “On Jordan Peterson.”1 I liked that email, because it gave me the next step in the quest laid out in my Peterson piece. Essentially, the writer suggested that I look into Paul Thagard if I really wanted to see a good response to Peterson’s ideas.

The funny thing is that I quoted Thagard in my piece. I dismissed him offhandedly because he was dismissive of Peterson, but upon reflection, I’ve come to realize that isn’t enough.

While there’s certainly a correlation between dismissiveness and bad arguments, that’s not why Thagard’s argument is bad. Unfortunately, I didn’t realize that until my second read-through of his piece, “Jordan Peterson’s Flimsy Philosophy of Life.” So, if I want to show that Thagard is wrong, I have to take him seriously.

So, without further ado, Paul Thagard is wrong about Jordan Peterson because he doesn’t know how to read . . . in the literary theory sense of the phrase.

Part One: Literary Theory

It may seem weird at this point to break into a discussion of literary theory, but my objection to Paul Thargard is grounded in literary theory, so that’s where we’re starting.

I think the simplest way to approach literary theory is to talk about the problem it solves.

Let’s say you have to read a novel and write a paper on it for a class. A good-sized novel is around 80,000 words long. Your paper, written in Times New Roman, font size 12, double-spaced, one-inch margins, ten pages long, is about 3,300 words. The difference between the novel’s length and your paper’s length is going to greatly limit what you can cover in your paper.

Not only is there a space problem, but you also have to cover previous research related to the book and make significant arguments of your own. After those are included, direct quotations of the book may only take up a few hundred words in the paper.

Now you have a problem: which words from the book do you choose for your paper?

You could choose at random, but then it would be hard to form a cohesive argument.

That’s where literary theory comes in. Instead of trying to grapple with 80,000 words, a theory helps you strategically winnow all possible words, so that you can choose the best examples to support your argument in your paper. This process is sometimes loosely-referred to as “reading” a text. 2

This is a bit of a simplification, and I explained it through the lens of writing a paper instead of talking about a book in general, but the core principle remains the same. It’s hard to talk about everything that happens in a book in great detail, so literary theories are used to confine the scope of the discussion.

There are many theories to choose from. Marxist theory encourages the reader to focus on the relationships between different classes. Structuralism focuses on the form the novel, poem, or other work takes, and encourages the reader to ignore historical context and the author’s life. New Historicism takes the opposite approach and tries to understand the work within the context of the times in which it was written.3

There are upsides and downsides to each theory, but you can ultimately apply any of them to any work you want. The only difference between different theoretical examinations of the same work is that the theories will lead you to focus on different parts of the work and will ultimately lead you to ask different questions of it.

Because you’re asking different questions, you’re getting different answers about the work, even though the underlying work remains unchanged. Note that we’re not talking about truth. You can examine a fictional story without it being true, and the judgments literary theory asks you to make generally don’t require you to determine if the text in question is true or false.

Part Two: Scripture and Theory

The fun thing about the process I just described is that you can run it backwards, starting with the questions people ask, and work your way back to the theory they’re using.

When it comes to the questions people ask about scripture, that is, works that religions say contain spiritually-significant material, I believe that most questions asked fall into two categories. The resulting theories that are applied remain unnamed and undescribed, so I’m going to take a moment to describe them.

When religious people approach their own text, the theory they’re applying is “confirmational-instructional.” They’re attempting to attain the truthfulness of the work in question, whether spiritual or literal, and once that has been established, they’re attempting to figure out how they ought to live their lives. This is fundamentally unlike most literary theory, in that the readers are looking for truth in the text. Whether what they’re reading is true or not matters.

The flip side of this approach is often used by people who don’t see scripture as inherently holy or divinely inspired. The theory they’re likely applying is “disconfirmational.” These readers are looking for any contradictions, any inherent moral problems, or anything in the work which can’t be confirmed using outside evidence.

Like the previous approach, this one is also deeply rooted in a quest for truth. You can’t disprove something without having a counterclaim about what the truth is.

Note that these people are typically applying these theories without realizing that they’re applying them. But holy works are somewhat unique in that very few people read them for fun, in the same way that someone might pick up a science fiction or romance story.

Another important thing to note is that while the “conformational-instructional” and “disconfirmational” theories are the most likely to be applied, you can apply any theory you want to the text.

Marxist theory? Sure.

The results may be weird, but you can always apply the theory, because works are theory-independent.

Part Three: Joseph Conrad’s Hero with a Thousand Faces

Now that you have some basic understanding of literary theory, we need to do a quick deep dive into one theory. But before that, we must discuss Carl Jung.

Carl Jung was a Swiss psychiatrist, known in literature for his ideas about archetypes, which are ideas that lie in humanity’s collective subconscious. An example of an archetype could be that most cultures associate advanced age with wisdom, regardless of what continent they’re on. Things that fall into this category of “widely, mysteriously, and unexamined agreed-upon” are often archetypes.

In fact, stories themselves can be archetypal or take archetypal forms.

In some contexts, it’s called the “Monomyth.” Elsewhere, you may have heard it called the “Hero’s Journey.”

Popularized by Joseph Campbell in the book The Hero with a Thousand Faces, the Hero’s Journey is the idea that most stories, especially myths, have the same basic story elements. While the element manifests differently from work to work, the underlying framework remains the same.

The hero’s journey is characterized by the following stages. 4

- The protagonist receives a Call to Adventure

- The protagonist receives supernatural aid

- The protagonist overcomes a “Threshold Guardian” or a minor challenge and is launched into the unknown

- With the aid of a Mentor and/or Helper, the protagonist overcomes a series of increasingly difficult challenges and temptations

- In the “Revelation” stage, the protagonist symbolically or literally dies while overcoming their ultimate challenge and is symbolically or literally reborn, often transforming in the process.

- The protagonist atones for their own sins, or for sins they’ve inherited from their ancestors or society at large.

- Finally, they cross back over to the known and familiar, either returning home or coming to a place that is thematically similar to the place they left at the beginning of the story.

Many myths take this form, which is unlikely unless there’s something deeper happening.

There are many reasons that this could occur. Adherents to Campbell’s work, believe that there’s something fundamentally human about the ways these stories are structured. Since Campbell relied on some of Carl Jung’s ideas in developing his own, these commonalities are said to lie in humanity’s subconscious. As A Handbook to Literature puts it, myths are a “dramatic or narrative [embodiment] of a people’s perception of the deepest truths,” those truths that exist in the subconscious mind.

The Odyssey was one of the stories examined by Campbell while working on his theory. After applying his theories, one could say that The Odyssey is a story, but it also speaks to many deeper themes: love, familial duty, revenge, piety, and bravery. It’s the virtues a culture values imprinted onto a story.

These are things that still resonate today, despite centuries passing between when those stories were first told and us reading them today. While we may not have all the same virtues as the ancient Greeks, we seem to share the appreciation for the hero’s journey.

In fact, the hero’s journey is exploitable by modern writers. Just ask George Lucas, who read Campbell’s works before writing Star Wars, which is one of the purest modern examples of a hero’s journey in action.

In fact, the hero’s journey is so significant in literature that many experts consider analysis of it as one of the major categories of literary analysis. A Handbook to Literature lists the “Mythic” analyses as the eighth major theory grouping out of ten, saying it encompasses those theories “which [explore] the nature and significance of the archetypes and archetypal patterns in the work.”5

Part Four: How Jordan Peterson Reads Literature

One of the first comments I made to a friend after picking up Peterson’s work 12 Rules for Life was that Peterson reads literature like literature professors. That is, knowingly or not, he’s applying literary theory in his analysis.

What I didn’t know at the time, and what I didn’t realize until doing research for this piece, is that Peterson has some formal training in literature. He initially pursued a dual-major in political science and English literature during his undergraduate work, though he would only graduate with the political science degree intact, and would go on to study philosophy and clinical psychology in his postgraduate work.

So, it’s unsurprising that he has some familiarity with literary theory, but it may have influenced Peterson more than he realizes.

In his introduction to 12 Rules to Life, Peterson credits two sources on which he’s drawing to develop the book.

The first is a response to a question he wrote on the website, Quora, to the question “What are the most valuable things everyone should know?”

The response contains rough versions of the “12 rules” mentioned in the title of his later book.

But, how were the 12 rules developed?

These were outlined in the second influence Peterson cites, his previous work, Maps of Meaning, which is about myths. Peterson argues in that work that the “great myths and religious stories of the past, particularly those derived from an earlier, oral tradition, were moral in their intent, rather than descriptive. Thus, they did not concern themselves with what the world was, as a scientist or as a “disconfirmational theorist” might have, but with how a human being should act.

In short, Peterson is arguing, as someone who likes Campbell might, that the stories themselves have meanings encoded into them that are more profound than the stories themselves. Once you learn to look for these deeper meanings in the stories left by the ancients, you unlock a new layer of meaning that reveals how they thought you should live your life.

While the stories were told for entertainment, they have deeper messages about good and evil and how you should interact with them.

After reading 12 Rules for Life, I would argue that Peterson’s thesis is that “understanding the deeper meanings present in myth can improve your life and make you happy.” It’s a philosophical conclusion, but it’s deeply grounded in literary theory.

I believe he sees three general outcomes which depend on one’s relationship with these deeper meanings.

You can embrace them, unlock your fullest potential, and become happy.

You can fight them, which leaves you weaker than you could be, and probably unhappy, too.

Or, you can reject them altogether. While this area could use further explanation, in my opinion, Peterson sees those who reject these meanings as particularly vulnerable to oppressive, totalitarian regimes, like communism and fascism.6

Even if you disagree with him, I think most honest people would have to admit that it’s an interesting take on things, especially in an age where people are becoming more authoritarian at an alarming rate.

Why Paul Thagard is Wrong about Jordan Peterson

Paul Thagard doesn’t get archetypes.

Or, at least, he doesn’t understand the fundamental difference between reading scripture in a literalistic sense and reading it in a literary sense where one is looking for underlying meaning.

Here’s a quote from Thagard’s article “Jordan Peterson’s Flimsy Philosophy of Life:”

“Peterson’s rules for life are intended to tell people what they ought to do, not just what people actually do. They concern morality, which raises the important philosophical question of the basis of ethics. Peterson’s answer looks to religion, in particular Christianity . . . [t]his connection of morality with religion justifies his frequent use of Bible stories such as Adam and Eve in his discussions of how to act.

“But philosophers since Plato have recognized many problems with basing ethics on religion.”

What’s particularly interesting about this is that Thagard seems to be locked into the state of mind that there are only two ways to approach religion, which happen to be the ones we discussed earlier. In his eyes, you can either apply “comfirmational-instructional” or “disconfirmational” theories.

Thagard finds the fact that Peterson isn’t applying disconfirmational theory a serious problem. This reveals his total ignorance of literary theory. There is no “correct” theory to apply to a given piece.

Worse, Thargard seems to miss the breadth of stories that Peterson uses in his arguments. Religious myths are only a subset of the stories he examines.

Looking in the index reveals sources as varied as “Pinocchio,” Animal Farm, The Brothers Karamazov, the Buddha, the soap opera Dallas, the pre-Christian myth Enuma Elish, Disney hit, Frozen, just to name a few, as well as a number of Renaissance painters and sculptors and a number of modern philosophical, psychiatric, and scientific works and studies.

After seeing how many works Peterson considers, it’s hard to escape the conclusion that Thagard’s stance is reductionist.

At our least generous, we have to wonder if Thagard actually read Peterson’s book. Certainly, scripture is a major player, but it’s only one player among many, and a work shouldn’t be disqualified merely because it analyzes scripture.

But, Thagard literally says “Peterson’s answer looks to religion.” That claim is at least misleading, but it may be more accurate to say that it’s outright false.

Imagine for a moment that arguments are like skyscrapers. Each plank in the argument is a floor in the skyscraper, and the penthouse suite contains the conclusion. If you prove that any plank is false, then the levels above that floor collapse.

Peterson’s arguments are somewhat unique in that the skyscraper they build it shaped like an “A.” One leg in that A represents his philosophical arguments. The other represents his literary argument. The penthouse at the top balances on both legs.

Thagard only sees the philosophical leg of the tower, and only sees the religious parts of the other leg. Despite the fact that there’s more to the picture, he still condemns the whole tower as destined to fall.

If we’re generous, we could suggest that someone with formal education in philosophy has preconceptions about what arguments look like. Maybe Thagard just isn’t ready to tangle with an argument that doesn’t look like the others in his field.

Peterson has a response to people like this in his book. After a short discourse on the two creation stories in Genesis 1 in the Bible, he says the following.

“Because we are so scientific now—and so determinedly materialistic—it is very difficult for us even to understand that other ways of seeing can and do exist. But those who existed during the distant time in which the foundational epics of our culture emerged were much more concerned with the actions that dictated survival (and with interpreting the world in a manner commensurate with that goal) than with anything approximating what we now understand as objective truth.”

That’s on page 34 of Twelve Rules for Life. Not only does it confirm to some extent what I was saying about Peterson’s use of literary theory as a critical part of his argument, it reveals that he doesn’t even consider scripture to be objective truth.

That means that Peterson’s answer can’t “[look] to religion” as Thagard so blithely suggests. It’s not the only source on which Peterson draws to form his arguments, but even if it were, he doesn’t even believe it’s true. This aligns with the fact that Peterson is typically described as an agnostic.

Because he misses the literary side of what Peterson is doing, Thagard ultimately ends up arguing against shadows of his own design. They resemble Peterson, but they’re something less than the real thing.

Thagard’s strawman is very convincing if you haven’t read Twelve Rules for Life. The second you do you’ll realize there’s so much more in it than Thagard claims.

It might sound like I’m hammering the same point home over and over again, but there’s a method to the madness.

Remember the simile about towers and arguments?

Thagard’s claim that “Peterson’s answer looks to religion” is part of the ground floor of his argument-tower. I have multiple objections to what Thagard argues, but if the ground floor crumbles, the rest of the argument goes with it.

I think I’ve cast significant doubt on Thagard’s claim about Peterson and religion. Combine that with his complete obliviousness to literary theory, and we have a theory that doesn’t stand up to scrutiny.

To be fair, he’s a philosopher and you wouldn’t normally expect him to talk at length about literary theory. But, that’s one thing among many that he missed, and at some point you have to stop making excuses for people you disagree with and admit that they did a bad job.

If you liked this post, be sure to check out:

Characterizing the Intellectual Dark Web

On Jordan Peterson

What Makes an Idea Dangerous?

- I’ve learned a lot since then, and I wouldn’t give the piece the same title as it has now. Somehow, it highly ranks for the search term “paul thagard jordan peterson”, which is strange given that I only mention Thagard once in the piece, in passing. Obviously, my search engine optimization wasn’t as good as it is now.”

- Why people obsessed with books, such as myself, are so imprecise with their words is something of a mystery.

- Of course, there are far more theories than these three.

- There is of course, debate on the exact nature of these stages, and I’ve somewhat simplified the discussion to make it easier to read. Campbell himself argues there are 17 stages.

- Page 142

- Of course, there are reasons he gives for this, but that could be covered in a whole separate piece, or it might just be better to go read his book.